Saorsie the Shepherdess

Yesterday, I took the train north to begin a weeklong stay at the Hudson Valley Writers Residency. For my train reading, I brought along the book Learning to Look at Sculpture because I have been searching for a primer on sculpture in order to grow smarter for the Mark di Suvero sections of the dog café book. (I have decided on the title We Live in Hidden Cities, but its every day title is “the dog café book” or, as a texting friend typo-ed to me recently, “dog cage.”) I didn’t learn much about sculpture beyond “it is an art form with which we share space.” I fell into conversation with my Amtrak seatmate, a handsome young woman in the vein of Julia Stiles.

Readers are reminded that the description of this website contains the phrase “champion of the chance encounter.”

My seatmate was on the last leg of her trip home from Scotland, where she had gone on an Outlander tour. (“Lallybroch!” “The Battle of Culloden!”) I am fluent enough in Outlander (the show, not the books) and then we branched into various things Scottish. I told her that it is my ambition to do a residency at Hawthornden Castle outside Edinburgh, and that I was on my way to a residency for the week. What am I working on? The history of one block in my neighborhood. She told me that she was majoring in history and had recently written a paper about how women’s history, so often obscured from the written record, can often be found in textiles. She attends SUNY Empire, an online program, which enables her to help out on the family farm, further upstate, where her family raises livestock, mainly sheep.

It struck me that leaving a sheep farm to vacation in Scotland was something of a busman’s holiday. I didn’t say this to her because she is 20-something and I doubted that she would know the term.

Instead, I said, “So you’re a shepherdess.”

Her mother is writing an historical novel about the family farm. I am all for historical novels (having written one and having one in a state of benign abandonment) and read over the summer Ben Shattuck’s The History of Sound, which a poetry professor at MY SUNY program told us was a collection of short stories written in a form called hook-and-chain, a form popularized in New England in the 19th century, which follows the pattern a bb cc dd ee ff a. I recommended this book to the shepherdess, along with Andrea Barrett, who I recommend to everyone. She didn’t write any of this down – I was a stranger on a train bothering a young woman who’d flown to JFK from Scotland, then taken the Long Island Rail Road to Penn Station to get an Amtrak to take her upstate to her farm. But maybe she will see this.

Champion of the chance encounter.

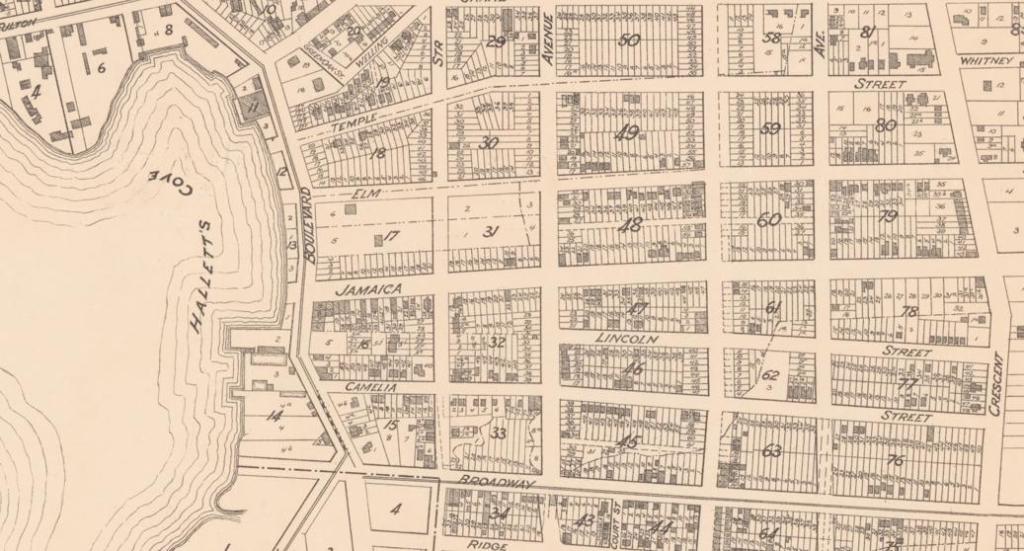

Earlier this summer, I visited the Queens Historical Society to see if I could get an answer to the question, “What was that parcel of land that juts into the East River between the time it was Stephen Halsey’s house and the time it was turned into NYCHA Housing?” I looked at maps and chatted with Jason Antos, the historian on site. Then since I was on the 7 line anyway, I took the 7 train to the Trader Joe’s in Long Island City, where I wound up chatting with the cashier as she checked me out. She too is a history student and had written a paper on the history of the Gowanus Canal. She later read this very blog and sent me a brief history of remonstrances, which I had been in search of, curious as to whether there was a precedent for the Flushing Remonstrance, or whether that particular set of early Long Islanders came up with the idea of writing a public letter to Peter Stuyvesant to protest his religious intolerance. (They did not come up with it. Remonstrances were a thing going back to King John of Magna Carta fame, according to the historian currently working the cash register at the Long Island City Trader Joe’s.)

Historians are everywhere, might be the moral of this post. Or, it pays to talk to strangers. Also to carry a business card.

Shzu Shzu

The café was a new one for me, so small it seemed I could hold it in the palm of my hand. It was called, fittingly enough, Café Sparrow. As I sat with my morning coffee and notebook, I was accompanied by the conversation between a man and a woman at a table an arm’s length away. Had I been at my usual café, I would have been overhearing a conversation in Greek. But I was one avenue and seven streets away from my usual spot and in Astoria, that distance takes you over a border into another country.

I suspected they were speaking Serbian. I’ve often thought that if cats developed the ability to speak like a human, the language they would choose would be Serbian. The rolled R’s and the shzu shzu consonants would prove so easy to navigate. As for the breakfasting couple, I loved the sound of their language. I would have asked them what it was. But I was afraid they would think I was from ICE.

Long ago in civics class, we were assigned to write a term paper on one of the federal agencies. (Nearly every part of that sentence is hopelessly quaint.) I chose, as it was then known, the Immigration and Naturalization Service – INS. One of the stated objectives of INS, created by FDR in 1933, was to “supervise the immigration process.” In 2003, as part of the Homeland Security Act, ICE was created – Immigration and Customs Enforcement. One of the stated objectives of ICE is to operate the “removal process.” For “naturalization,” (to become a citizen is to become “natural”), you must go to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. But you don’t hear much about USCIS, and perhaps I should not have mentioned it.

Some people fond hearing a language that is not English “uncomfortable.” I have in my time been made uncomfortable by language. When I was at CBS, my first job out of film school, my boss used to leer at me with his palm against my neck, “Oh, if I were ten years younger.” This made me uncomfortable. When my father, responding to my complaint about this behavior, replied, “Can’t you put up with it?” I was uncomfortable. When the HR assistant at ABC, shaking her head at my resume which included my degree, two years under siege at CBS, and a novel under contract from a prestigious publisher, told me “Only secretarial positions are available,” I was uncomfortable. (And skeptical.)

But that was language directed at me specifically, and I am using “language” here in the definition “choice of words” not “a system of communication used by a particular country or community.” Although I was made uncomfortable by the latter definition when I worked at an Italian law firm (having switched industries, feeling no love or money from television) and two people conversing in English in front of me, gave me the side-eye and switched to Italian. That behavior was deliberately exclusionary, as opposed to the Serbian couple at Café Sparrow, who were merely conversing.

I wanted to ask merely, “Hey, what language is that? It’s beautiful.” I remember asking a man in a wine store “Are you speaking Portuguese? Such a beautiful language.” I guess I’m not made uncomfortable by the sound of other languages. I guess I have no conclusion to offer that isn’t naïve or too hopeful or too bleak. I guess I am fond of the sound of purrs and shzu shzus.

Where the Streets Have No Name

My friend Lee once sent me a card that came back to her because she had misaddressed the envelope – nearly all the streets in Queens are numbered and many share a number, so that there is a 31st Avenue, Street, Road, and Drive within walking distance of me. All of the roadways once had names, of course, and they were all changed to a numbering system.

In 1898, Queens County decided to consolidate with Manhattan. While Brooklyn was an entire city when it joined Manhattan. Queens was a county of small villages, each with its own Broadway, its own Main, its own Elm.

A one-time official Queens Historian wrote: “By the 1920’s, in order to rationalize the maze of gridlets and ensure connectivity of the system, the Queens topographic bureau imposed an evenly spaced master grid over the entire borough. Streets began in the west in Long Island City and Avenues began in the north in Whitestone. . . named streets followed the contours of the land.”

That does not appease Lee, who still stings from the return of her greeting card. But it was Lee I thought of as I read through the minutes of the Board of Trustees of the Village of Astoria, 1839-1870 last week at the New York City Municipal Archives.

About a year ago, a man whom I don’t know and didn’t ask informed me on social media that the history of Astoria begins with Stephen Halsey. This unasked man is correct, I suppose. The history of the land does not begin with Halsey, but the history of Astoria does – it was incorporated by the New York state legislature in April 1839, and Halsey is the reason it is named Astoria. Halsey was a fur trader who was chummy with John Jacob Astor, which I suppose it was necessary to be if one was a fur trader at that time. But here I will defer to Rebecca Bratspies, a professor of environmental law at CUNY Law School and the author of Naming Gotham: The Villains, Rogues & Heroes Behind New York’s Place Names:

Stephen A. Halsey, founder of the Astoria neighborhood of New York, proposed naming the town after John Jacob Astor in the hopes that Astor would make a large donation to a young ladies’ seminary, which would also be named after him. Astor made the donation, but instead of the generous support Halsey had been hoping for, Astoria donated only $500 to the Astoria Institute . . . Astor himself never visited Astoria, even though he could see it from his country house on the other side of the East River.

Halsey is all over these early years, according to the minutes. I thought that minutes of a board of trustees would be dull reading, that I would be finished by lunch and on my way to the rest of my day off from the office. And they were dull reading – the building of walls, sidewalks, sewers, the maintenance of wells and pumps, the grading of streets, the placement of street lamps, the establishment of a fire department, the naming of a police constable. But they were also fascinating and kept me there until the archives closed, as I read the story of transformation from a bunch of farms and fledging factories being shaped into a town. Many of the early meetings were held in Halsey’s home.

And then I came upon the naming of the streets. Lee would rejoice!

“RESOLVED that a new street sixty feet wide to be designated as “Grand Street” shall be laid out and opened commencing at Welling Street and running in an easterly direction as far as the village limits extend along the line between the lands of C. B. Trafford and B R Stevens on one side and R M Blackwell – Buchanan & Gabriel Marc on the other side . . .”

Also established in these early minutes: Main Street, Flushing Avenue, Newtown Avenue, Sunswick Terrace, Greenock Street, Welling Street, Emerald Street, Linden Street, Woolsey Street and Remsen Street. Grand Avenue (not street) is now a subway stop, Remsen is 12th Street, Welling is Welling Court, Sunswick is a buried creek, and Newtown Avenue is Newtown Avenue. The rest would require some digging.

Certain prohibitions were also introduced: no person shall allow his livestock or fowl to wander at large, set off gunpowder or combustible material in public places, swim in the East River near the ferry slip or appear naked in a public place, or “raise or fly a kite in any street lane or alley within the village under the penalty of Five Dollars for every offence.”

I wondered what the deal was about flying a kite. There were no telephone lines to disrupt in 1848, and I doubt that there were all that many kites. I would have asked the friendly archivist, Marcia, but Marcia, who is from Flushing, had already hurried away to find a law dictionary when I asked her about the Flushing Remonstrance. I know about the Flushing Remonstrance; it was that word “remonstrance” that has bothered me. Were there other famous remonstrances?

There were remonstrances in the board of trustee minutes. A farmer remonstrated that the location of Grand Street would destroy some of his trees. The Hook and Ladder company remonstrated that the proposed Village Hall should not be in the firehouse.

More exciting to me than the evidence of other remonstrances was Marcia, the archivist, who responded to my questions with lots of information – files dug up, an Excel spreadsheet of other sources emailed to me, suggestions as to where other information might be housed. I hadn’t realized how parched I was for a sympathetic ear until she provided a gentle sprinkling of support. Writing is a lonely business at the best of time; writing researched nonfiction when one is not a journalist or historical can seem deranged.

“How’s your history of Astoria coming along?” smirked a work colleague at a recent lunch. Granted, this particular colleague can make the response to a mild “How are you?” sound scathing, but this dash of scorn reminded me to be careful who I tell (as my fellow writer but not relative Joan Frank once advised).

I know, I know. Be grateful for the librarians, the archivists, the other lonely historians, the kind stranger who gave me permission to quote from her PhD thesis on Mark di Suvero. Be grateful, and tell the naysayers (quietly, of course) to go fly a kite.

“Poetry makes nothing happen” . . . but poets laureate do

Last month, I sailed down the East River and across New York Harbor to attend the New York City Poetry Festival, which is held annually on Governor’s Island. This journey required two ferries. On the second ferry, I met Phylisha Villaneuva, an MFA candidate in poetry at St. Francis College, and the poet laureate of Westchester County. I asked her how she had obtained the position of poet laureate of Westchester County, and what the job entailed. The answers, in order, were: she applied, and the usual – a tenured appointment, a small stipend, the performance of readings, the teaching of workshops and a commitment to the enthusiastic promotion of poetry in the community whenever an opportunity arose.

I had no doubt Phylisha would fulfill these obligations. She could not contain her excitement about her upcoming reading at the festival, her MFA program, and the beauty of the very hot day, an enthusiasm which did not diminish even when we discovered that we had taken the wrong ferry to the island. Apparently, there are two ferries to Governor’s Island and the one we took, which leaves from Pier 11, what you might call the Grand Central Station of the ferry system, left us at the spot on the island that was possibly the further possible point from where the festival was taking place, which was near the other ferry, the one that leaves from the Staten Island Ferry terminal.

I was there to help man the table for Poets of Queens while they performed in their allotted time slot, but since I took the wrong ferry and wasted time roaming the island, lost, I arrived to an empty table. While poets from three competing stages orated in the distance, I unpacked the t-shirts (which you can find here) and the group’s most recent anthology (which you can find here).

I am not a poet of Queens. I am studying poetry and I live in Queens. But Poets of Queens, which is run by Olena Jennings, is a group that helped me make the transition from novelist of historical fiction about WWII Bermuda to flaneuse chronicling pandemic-era Astoria. I’ve attended several of Poets of Queens’s readings at QED Astoria. (During the pandemic, I had to go local, and when I went local, I went deep.)

At one of the readings this year, I heard poetry read by Maria Lisella, the poet laureate of Queens.

Didn’t know that Queens has a poet laureate? It does. So does the Bronx (Haydil Henriquez), Brooklyn (Tina Chang), and Staten Island (Marguerite Maria Rivas). I couldn’t find a poet laureate for Manhattan, although New York State has one in Patricia Spears Jones.

What I learned today is that Maria Lisella would like to step down from her role as poet laureate of Queens. The same weekend that I travelled to Governor’s Island, Lisella wrote a letter to the Queens Gazette, pointing out that the installation of her replacement in the role is long overdue. “Traditionally,” she wrote, “Queens Poet Laureate candidates were interviewed and judged by a team of local poets, representatives from Queens’ cultural organizations, colleges such as: St. John’s University, Queens College, as well as the Queens Council on the Arts, Queens Museum, Queens Theater, thus creating a broad base of contacts for the incoming Queens Poet Laureate.”

Her letter ended with a call to action that others write to Queens Gazette to encourage the Borough President to act upon this next appointment. This call was answered by Bruce Whitacre, a fun and generous poet with a new book out, by KC Trommer, founder of Queensbound, “ a collaborative audio project founded in 2018 that seeks to connect writers across the borough, showcase and develop a literature of Queens, and reflect the borough back to itself,” by poet and librarian Micah Zevin and by Dr. Tammy Nuzzo-Morgan, poet laureate of Suffolk County.

Apparently, letters to the editor at the Queens Gazette are addressed to QGazette@AOL.com.

In case you’d like to join the ranks.

Kicking and Giving

I have now completed the second week of my fully-remote life. My previous job had a one-day-a-week-in-the-office policy for those of us in IT. For some reason, although I was in the research library, I was umbrellaed under IT. (My inability to master layout in the upgraded version of WordPress tells you allyou need to know about me working in an IT department.) When I asked my boss why the library was IT, his reply was “Gotta put us somewhere,” which effectively sums up what led me to leave that job — the lack of engagement, the listless dismissal of legitimate inquiry. The loneliness. In my new role, I am back to research umbrellaed under business development, which sets the world right again, but it is fully remote. Although this is only the difference of one day a week, it is a mindset which sets the mind reeling. To ward off the loneliness, I have committed myself to Pilates and knitting, two things at which I will be terrible for the foreseeable future, but both of which are within walking distance (there are two knitting groups that meet at different bars. I know one stitch.)

And then daily, I take long walks and write in a coffee shop. There is Chateau le Woof, of course, but nearer to home, so that I can get a walk-and-write in before logging on to work, there are three cafes: Under Pressure, Madame Sou Sou and Astoria Coffee. Under Pressure has a high-tech, sleek European vibe, a business-district-transformed-from-its-industrial-past-near-a-branch-of-the-Guggenheim-and-a-W-hotel kind of Europe. Madame Sou Sou has an Old Town European vibe, a cafe-on-a-narrow-street-full-of-quaint-shops-that-are-always-closed-recommended-by-the-landlady-at-your-AirBnB kind of Europe. Astoria Coffee has no European vibe at all. Extremely small even by NYC standards, it is resolutely Astorian, patriotically displaying on its limited wall space art photos of Astoria taken by local photographers.

But it is at Under Pressure where I set my first scene.

Despite its only-in-town-for-fashion-week interior, its clientele is mainly Greek and mainly working class. There is outdoor seating where you can watch the elevated train go by, or watch people line up to order gyros from the Greek on the Street food cart, or watch a traffic cop strolling down the avenue looking for victims. Under Pressure’s employees are Greek,and if their highly amused reactions at my attempts to greet them in their native tongue are any indication, no amount of living in Astoria will help my accent. I was sitting outside with my coffee and my notebook, earbuds in but podcast off. Three men were seated behind me, Queens natives by their accent, contractors by their conversation.

Guy on phone: “Look, I told you I needed you to have the bathroom done by the end of the week . . . that ain’t my problem. . . do what you gotta do. Come in early, stay late, get it done.”

I returned my focus to my to-do list, writing a list of what needed to be written, which is about all the writing I’ve done during the job transition. I heard a voice say “She’s not friendly,” and a moment later a man walked by, his Shiba Inu on a leash trotting alongside him.

Warning: the language below is foul but accurately recorded.

The first man said, “What the fuck! Not friendly!”

The second man said, “The fuck bring it out in public for if it’s not friendly.”

The third man said, “I’ll kick that fucking dog.”

At this point, I pulled out my earbuds and turned around.

The first man at least looked abashed. “Didn’t think you could hear with those things in.”

I explained that the Shiba Inu is a loyal-owner breed, until a few exchanges compelled me to stop. The second man muttered “Shiba Inu,” like it was a new obscenity to welcome into his lexicon. The dog kicker said “I got a pit bull. He don’t like people, I don’t take him outside.”

I held up my palm in the universarl signal for “I will now exit this conversation” that in this case meant “I have no wish to play the extra in a community theater production of Goodfellas.”

Later in the week, I sat at Madame Sou Sou with my coffee and notebook writing about the Under Pressure encounter when I found myself within earshot of a coffee date, a young American man, a young European woman, awkward (“I like your shoes”) and endearing. He explained that he would spend the next day at a “Friendsgiving” and I happened to lift my head in time to see her tumble the phrase in her mind, extrapolating from her familiarity with “Thanksgiving” as a North American holiday to ask “What is a ‘giving’?” .

As he explained, I entertained the idea of a “giving,” a celebration where people gather out of choice, not obligation, not freighted with travel rushes and mandatory dishes, expectations, disappointments, grudges, too much stuffing, stuffing of everything.

So, my friends, I wish you a good giving. (But no kicking.)

Is there a place that means a lot to you?

Yesterday I conducted the second of my readings/workshop at Chateau le Woof. It was, New York-famously, the seventh consecutive Saturday of rain, so my expectations of attendance were low. Who would venture through more sogginess to attend a reading of a work-in-progress advertised by an admittedly cute but somewhat vague flyer?

Yet, people came. One was my friend Tess, who I met at the VCFA conference last August, her friend Hannah, two kind neighbors, and a woman who I met in the most interesting manner. This work-in-progress has been a work-in-progress, as I shift and distill its focus from so many tantalizing possibilities. Initially, I began visiting the Chateau le Woof (aka “the dog cafe”) just after the vaccines were rolling out, in the late spring of 2021. I was privileged enough to be able to work from home, but also stir-crazy enough to need to be somewhere other than my home, with other people, yet not indoors. The dog cafe, an indoor-outdoor space, was perfect. I reflected on how we had quarantined ourselves during this pandemic, but during previous epidemics, New York City had quarantined the sick on the islands surrounding Astoria — Roosevelt Island, previously known as Welfare Island and before that Blackwell’s Island, had been home to hospitals, jails, poorhouses and a notorious lunatic asylum. North Brother Island had been home to a tuberculosis hospital. Hart Island was a potter’s field begun after the Civil War and in active use during the height of the pandemic, where graves were dug for the unclaimed dead by the unhappy residents of Riker’s Island.

I still have a draft of that chapter — “Exiles of the Smaller Isles” — but realized I could not use the background research I’d done on Typhoid Mary. She was sentenced to life on North Brother Island, not in the tuberculosis hospital (where she worked as a lab assistant) but in her own small cottage from which, in the imagination of novelist Mary Beth Keane in her novel FEVER, Mary falls asleep to the sound of the rushing currents of the Hellgate, a rapid, still-dangerous stretch of the East River between Ward Island and Astoria. FEVER is an excellent if bleak novel detailing the options of an unmarried immigrant woman at the end of the 19th century. At one point, the caretaker on North Brother Island points out to Mary that her life in her tiny cottage with her little dog, however lonely and powerless, is still much better than some have it.

My favorite of these books was TYPHOID MARY: AN URBAN HISTORICAL which was surprisingly hard to get a hold of, considering its author, Anthony Bourdain. It is top-of-the-game Bourdain, scathing and snappy, but I had to get it on Kindle, because it may be out of print. So it was not among the stack of books I took to the closest Little Free Library. I deposited them and at the same time was delighted to see that the small wooden box held a copy of UNCOMMON GROUNDS, a history of coffee, which was on my list of books I needed for research.

Another woman browsing the Little Free Library eagerly grabbed ALL the Typhoid Mary books, with such enthusiasm that I tilted my head at her. She explained that she was an epidemiologist with the New York City Department of Health.

“So . . . how was your pandemic?” I asked.

She attended the reading, along with her friend, another epidemiologist.

I started keeping this blog such a long time ago that I forget my own logline sometimes, which ends with “champion of the chance encounter.” This was one, if ever there was one.

Mark di Suvero meets the Golden Gate Bridge

I haven’t been posting as often as I would like because I’ve been buried in research for my book about the history of the section of Astoria you can see from Chateau le Woof. The project was previously known as “Summer of the Dog Cafe” but it seems to have morphed into a book and it involves Hallett’s Cove, the former Sohmer piano factory where the dog cafe occupies part of the ground floor, and Socrates Sculpture Park, founded by Mark di Suvero, and Spacetime, the red warehouse which di Suvero uses as workspace. Teaching myself about the Puritans, the history of pianos in New York City, and the rise of public art and then trying to turn it into prose has been a slow process! It took me forever, it seems, for example, to come up with the opening paragraphs of the chapter on Mark di Suvero, but here they are for your appraisal.

In 1941, a family left China to sail across the Pacific, fleeing a war that would not be fled. Although they had been living in China for years, the family was Italian. The father, a naval attaché, was Venetian, as was the mother, a former Countess. With them were their four children, each of whom faced radiant destinies: an activist lawyer who would establish a law school, an art historian, a poet and a world-renowned artist.

Let’s envision the future artist, nine years old, on the deck on the S.S. President Cleveland. His hands, wet with ocean mist, grip the railings as the Cleveland navigates from the great Pacific into San Francisco Bay. Here it is at last: America. America, named for an Italian explorer, just as he was, Marco Polo di Suvero. Perhaps he claps with excitement. We focus on his hands because his early public work will be of hands, clutching, opening, pointing.

Days of gazing at the endless blue of ocean and sky are suddenly broken by the terrible bright splendor of this span of steel, stretching across the bay for a mile, so long that the bridge never stops being painted. The last brush stroke on the south end in San Francisco serves as a signal to commence the next coat on the north end in Marin County. The color of the paint is International Orange. It flares into the eyes of the blue-blinded boy, himself an international fruit, an Italian raised in China entering America under a suspension bridge with towers so tall that they routinely disappear into clouds as though seeking the release of heaven. The bridge was begun the same year he was born, but it is only four years old, like a younger brother.

International Orange is a reddish orange firmly associated with the Golden Gate Bridge. But it is abundant on earth. We find it in the clay soil of Georgia, in the heart of a peach, in marigolds and goldfish, butterflies and autumn leaves, Irish setters and redheads. We find it in flames. But the color really belongs to the sky, in the grace of the sun rising and setting.

But who could imagine dousing a monument of steel with such a fierce, celestial color. The future sculptor Mark di Suvero, first encountering America, was too young to formulate such questions. He was just a boy, and what he most likely thought was “Golly, look at that!” or, more likely, “Che meraviglia!” But that encounter, and that thought, would direct the rest of his life, shape the course of the lives of dozens if not hundreds of other artists, and heavily influence the landscape of a certain stretch of Vernon Boulevard in Astoria, New York.

Dear David

Dear David,

Today I logged off work a minute early, because daylight is still precious, and I wanted to get out into it. I also wanted to walk by the Ukrainian Church which I have written about before, and which I can see from my living room window and which has been, if you get right down to it, most of my world view for the past two years. I face my monitor eight hours a day (not counting what I write when I write because I must write). If I turn my face to the right, I see the little altar of candles I have created to keep my spirits up. If I turn my face to the left, I see through the window the Ukrainian Church – that is, a little sliver of some magnificent stained glass window on the far left and then three stories of indifferent taupe brick and many many dull dormitory-like windows that I realized only during the pandemic were actually windows for a dormitory, for the monks who live there.

Yesterday I thought of visiting the church when I logged off work to set a candle in front of the locked gates. Remember after 9/11 all the makeshift altars in the neighborhood for all the cops and firemen who were then our neighbors? Remember our neighbor Joe the Fireman? I still remember cooking dinner on a Friday evening, on what must have been the 14th of September because the 11th was a Tuesday, and hearing a car door slam and Joe’s deep voice saying “Thanks.” He was thanking someone, probably a fellow fireman, for the ride home. He had been at “the pile” – remember that they called it “the pile”? – since Tuesday. His house had lost either 12 or 17 guys. I don’t remember. I remember calling down to him from my kitchen window, “Thank God you’re alright!” and I remember the absolute exhaustion in his voice as he stared up at a voice just as I was shouting down to a shadow.

Anyway, David, two other people had had my same idea, because there were two candles in jars in front of the gates. Unlit, because it was raining, and not inside the gates, because I have never seen those gates open, except when expelling a congregation, not open even during the Ukrainian Festival which shuts down that whole block of 31st Avenue so that beribboned braided girls can clog on wooden platforms while their counterparts, stiff, solemn boys in short vests, wait their turn to click and leap.

So, not the warmest church, the Ukrainian Catholic Church, no tentpole revival meetings or pancake breakfasts, but this is Astoria, after all, and the Greek Orthodox folks aren’t welcoming to outsiders, either. I walked on a block to see Con Ed soldering some metal plate over some hole they had dug up. They have been doing this for months, tearing holes into the street and then patching up, only to tear and patch again. I have theorized – since there is no one to talk to – that they are doing this because of the number of free-standing houses they are tearing down so that real estate developers can erect high skinny buildings where the shabby faux-Victorian houses used to be. Perhaps a greater strain on the Con Ed grid has inspired all this manic drilling and patching and ca-thunk-ing as traffic drives across the metal plates at night?

Anyway, someone was sealing a metal plate over a hole of the crew’s own making, and I watching the arc of the sparks, as one will watch arcs of sparks. A man in goggles saw me and shook his finger at me. He pointed two fingers to his own eyes, then to me. I walked away from him, a few steps before one of his begoggled colleagues shouted, “Don’t look at that! It’s bad for the eyes!”

You said, David, the last time I wrote about this church (see post “Saint Behind the Glass”) that you had never noticed the church, despite living so close to it for so many years.

Four years ago, before I left my terrible job, a fireman died on the set of a movie in the Bronx. His funeral was at St. Patrick’s Cathedral and attracted hundreds, if not thousands. Firemen and policemen, on motorbikes and on foot, filled Fifth Avenue, 57th Street, and other feeder roads. I was working in the GM Building at the time, at 59th Street and Fifth Avenue, and was coming into the GM Building from an appointment. I rode the elevator with a Young Turk of Private Equity who tapped both his foot and his phone.

“Is that the funeral for the fireman who died on the set of the Ed Norton movie?” I asked.

“Is what what?” he responded.

I explained: the roads shut down, the hundreds of uniformed men everywhere you looked, the absence of traffic, the sound of tolling bells.

“Huh,” he said, his thumbs still on his phone. “I didn’t notice.”

“Huh,” I responded. “And still there are so many people everywhere.”

“Isn’t it funny how I didn’t notice?”

“Funny is one word for it,” I said, and stepped off the elevator.

I wish this made me a hero, but of course I’m not a hero, and he no doubt dismissed me, as all the young people in my former and current department do, as some weird old dame (if they even use the word “dame”!) But that is a topic for another discourse.

I guess this topic is what to look at, whether or not it is bad for the eyes.

Longer letter later, as we used to say —

My Year in Reading

I’m not a full-fledged book critic, but I did review two books this year and provided a blurb for another. They are therefore disqualified (and indicated in italics) from my top ten. So, with the downtime I had at my disposal, and reading in periodicals, and listening to podcasts excluded, here are the books:

For research

When Breath Becomes Air – Paul Kalanith (N)

Breath – James Nestor (N)

300 Years of Long Island City History – Vincent F. Seyfried (N)

The Winthrop Woman – Anya Seton (F)

Insubordinate Spirit – Missy Wolfe (N)

The Wordy Shipmates – Sarah Vowell (N)

Asthma: A Biography – Mark Jackson (N)

Damnation Island – by Stacy Horn (N)

The Other Islands of New York City – Sharon Seitz and Stuart Miller (N)

Fever – Mary Beth Keane (F)

Typhoid Mary: Captive to the Public’s Health – Judith Walzer Leavitt (N)

The two ongoing projects here are an essay on breathing and other people’s attitudes towards a person unable to breathe, and a memoir/local history/I don’t know about the little area in Astoria where I live, the dog cafe which I began to frequent as soon as I felt it was safe to mingle again, and the history of the islands around Hallett’s Cove. The Winthrop Woman is a fictional account of Elizabeth Fones Winthrop Feake Hallett, a well-connected Puritan woman whose marriage to William Hallett, scandalous in its day (1650 ish), necessitated the “founding” of Astoria, which meant that a Dutch governor gave an English newcomer Lenape land to farm. Insubordinate Spirit is historian Missy Wolfe’s excellent nonfiction account of the same events, with a larger cast of characters and less romance. Similarly, Fever and Typhoid Mary are fictional and factual accounts of the life of Mary Mallon.

Wish me luck as we wave 2021 goodbye on making meaningful progress on these projects.

Fiction

Actress – Anne Enright

Euphoria – Lily King

The Heavens – Sandra Newman

Convenience Store Woman – Sayaka Murata

The Cold Millions – Jess Walter

Better Luck Next Time – Julia Claiborne Johnson

Meet Me in Another Life – Catriona Silvey

Humane – Anna Marie Sewell

V is for Victory – Lissa Evans

We Run the Tides – Vendela Vida

Light Perpetual – Francis Spufford

Interesting Women – Andrea Lee

Hamnet – Maggie O’Farrell

A Thousand Ships – Natalie Haynes

A Snake in the Raspberry Patch – Joanne Jackson

This Must Be the Place – Maggie O’Farrell

The Vanishing Act of Esme Lennox – Maggie O’Farrell

Instructions for a Heatwave – Maggie O’Farrell

We Want What We Want – Alix Olin

Matrix – Lauren Groff

All’s Well – Mona Awad

Cloud Cuckoo Land – Anthony Doerr

The Book of Form and Emptiness – Ruth Ozeki

Harlem Shuffle – Colson Whitehead

The Hand that First Held Mine – Maggie O’Farrell

The Great Circle – Maggie Shipstead

Self-Care – Leigh Stein

The Plot – Jean Hanff Korelitz

I read Hamnet in the food court at LaGuardia Airport, where I arrived at 6 a.m. to learn that my flight on the Fourth of July weekend had been delayed twelve hours. Even the association of reading that book with the every-fifteen-minutes rendition of “New York, New York” played to the performing water fountain, and the tears I shed over Hamnet while wearing a mask could not diminish the experience. I made it a mission to read everything else Maggie O’Farrell has written. The only reason her other novels are not bold-faced is that they sort of cancel each other out, like Academy Award nominees for Best Supporting Actor, and besides, her memoir is bolded as well (see below).

The other bold-facers are the familiar names of the year, with the exception perhaps of my Stonehouse sister-novelist Anna Marie Sewell, who somehow blends a tale of a First Nations detective hunting down missing women with a lycanthropic romance, and Lissa Evans’s V is for Victory because it is the third in a charming trilogy of an unlikely found family during WWII.

Memoir

Ghostbread – Sonja Livingston

Ladies Night at the Dreamland – Sonja Livingston

Recollections of My Nonexistence – Rebecca Solnit

I Am I Am I Am – Maggie O’Farrell

The Good Poetric Mother – Irene Hoge Smith

I had hoped to do a workshop with Sonja Livingston at VCFA, but when the confeence went virtual, I folded like bad origami at the thought of doing another Zoom workshop. I had already done a novel workshop, and am part of a program called New Directions which blends psychoanalysis and writing, introduced to me by Irene Hoge Smith, the daughter and author of The Good Poetic Mother. New Directions streams for three intensive long weekends three times a year.

I loved I loved I loved I Am I Am I Am, a unique and compelling structure for a memoir.

Nonfiction/Essays

The Celeste Holm Syndrome – David Lazar

The Unreality of Memory – Elissa Gabbert

Pain Studies – Lisa Olstein

Nonfiction/Other

Letters on Cezanne – Rainer Maria Rilke

A Poetry Handbook – Mary Oliver

I decided to re-read Rilke’s thoughts on Cezanne ahead of the exhibit on Cezanne at MOMA.

Cozy old things and mysteries

The Enchanted April – Elisabeth von Arnheim

Pretty as a Picture – Elizabeth Little

The House on Vesper Sands – Paraic O’Donnell

Dear Daughter – Elizabeth Little

High Rising – Angela Thirkell

Before Lunch – Angela Thirkell

The Women in Black – Madeline St. John

In the Bleak Midwinter – Julia Spencer Fleming

All the Devils Are Here – Louise Penny

Death at Greenway – Lori Radnor-Day

Castle Bran – Laurie R. King

Clark and Division – Naomi Hirahara

And there you have it. I will close out the year with Rebecca Solnit’s Orwell’s Roses, which I find slow-going because I often have to close the book in envy and contemplation and reconsider my life choices.

I have a smallish stack of friends’ books I have not yet been able to read, and they are moving from the pile to the list in the coming year. I recognize the utter lack of poetry books, except for the one craft book, on my list, because I tend to read poems as individuals and not as part of a collection, but I am happy to take recommendations.

I am also still looking for literature which takes place in or contains scenes which occur in Queens, so if you have any thoughts on those, send them my way.

Desperation Park

It is not merely community that we miss, but spontaneous community, the casual hang, the chace encounter which, as my WordPress legend has it, I am champion of, or used to be, when chance encounters were not a public health threat. “Don’t be so friendly to strangers,” a former friend once admonished me. “It’s weird.”

It is not merely community that we miss, but spontaneous community, the casual hang, the chace encounter which, as my WordPress legend has it, I am champion of, or used to be, when chance encounters were not a public health threat. “Don’t be so friendly to strangers,” a former friend once admonished me. “It’s weird.”

She said it in this very park, where I sit and write this, the park I came to visit, Socrates Sculpture Park, five acres by the waterfront, reclaimed some decades ago from industrial landfill. In addition to large outdoor sculpture, it hosts, in the summer, all manner of exercise class and artistic offerings: cinema nights, concerts, dance performances and Shakespeare al fresco. It was at the latter, when I was picnicking and offered the group at the adjoining blanket part of our nosh that my friend chided me:

“Don’t do that, don’t talk to people all the time,” she said. “It makes you look desperate.”

Desperate to get back to normal, desperate to venture beyond our walls, desperate to transcend social distancing for human connections outside our “pods.” Desperate to shed our masks (if only to then don the social ones we used to wear: “a face to meet the faces that we meet.”). Or is that a desperate reach for a metaphor?

Perhaps I am desperate. Perhaps we all are.

I know that this park, on a chilly Sunday afternoon one week before daylight savings time comes to alleviate at least a small fraction of our darkness, is full of my neighbors (or, if you prefer, “strangers”) in masks and down coats, attempting to hasten spring by behaving as though it is already here.

I came to the park today to photograph the sculpture “Proposal for a Monument (Two)” by Fontaine Capel. I attended a Zoom talk by the sculptors in the new installation, and Fontaine Capel said that “Proposal for a Monument (Two)” represented the stoop of brownstones, which are being displaced by the glass-and-chrome building erected by real estate developers. We are not losing merely brownstones and stoops, but a place to sit and hang out with neighbors.

Neighbors hanging out in common places form what used to be known as community. When we lose community – the casual, sometimes vexing, occasionally inspiring presence of the familiar – what else do we lose?

After a year without it, we know what we have lost. And we are desperate to have it back.

Recent Comments