Saorsie the Shepherdess

Yesterday, I took the train north to begin a weeklong stay at the Hudson Valley Writers Residency. For my train reading, I brought along the book Learning to Look at Sculpture because I have been searching for a primer on sculpture in order to grow smarter for the Mark di Suvero sections of the dog café book. (I have decided on the title We Live in Hidden Cities, but its every day title is “the dog café book” or, as a texting friend typo-ed to me recently, “dog cage.”) I didn’t learn much about sculpture beyond “it is an art form with which we share space.” I fell into conversation with my Amtrak seatmate, a handsome young woman in the vein of Julia Stiles.

Readers are reminded that the description of this website contains the phrase “champion of the chance encounter.”

My seatmate was on the last leg of her trip home from Scotland, where she had gone on an Outlander tour. (“Lallybroch!” “The Battle of Culloden!”) I am fluent enough in Outlander (the show, not the books) and then we branched into various things Scottish. I told her that it is my ambition to do a residency at Hawthornden Castle outside Edinburgh, and that I was on my way to a residency for the week. What am I working on? The history of one block in my neighborhood. She told me that she was majoring in history and had recently written a paper about how women’s history, so often obscured from the written record, can often be found in textiles. She attends SUNY Empire, an online program, which enables her to help out on the family farm, further upstate, where her family raises livestock, mainly sheep.

It struck me that leaving a sheep farm to vacation in Scotland was something of a busman’s holiday. I didn’t say this to her because she is 20-something and I doubted that she would know the term.

Instead, I said, “So you’re a shepherdess.”

Her mother is writing an historical novel about the family farm. I am all for historical novels (having written one and having one in a state of benign abandonment) and read over the summer Ben Shattuck’s The History of Sound, which a poetry professor at MY SUNY program told us was a collection of short stories written in a form called hook-and-chain, a form popularized in New England in the 19th century, which follows the pattern a bb cc dd ee ff a. I recommended this book to the shepherdess, along with Andrea Barrett, who I recommend to everyone. She didn’t write any of this down – I was a stranger on a train bothering a young woman who’d flown to JFK from Scotland, then taken the Long Island Rail Road to Penn Station to get an Amtrak to take her upstate to her farm. But maybe she will see this.

Champion of the chance encounter.

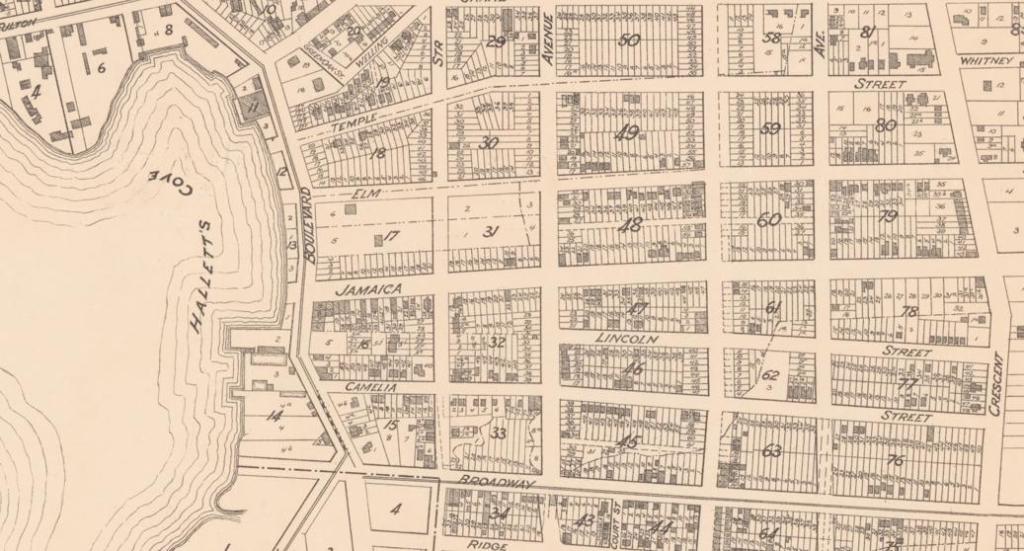

Earlier this summer, I visited the Queens Historical Society to see if I could get an answer to the question, “What was that parcel of land that juts into the East River between the time it was Stephen Halsey’s house and the time it was turned into NYCHA Housing?” I looked at maps and chatted with Jason Antos, the historian on site. Then since I was on the 7 line anyway, I took the 7 train to the Trader Joe’s in Long Island City, where I wound up chatting with the cashier as she checked me out. She too is a history student and had written a paper on the history of the Gowanus Canal. She later read this very blog and sent me a brief history of remonstrances, which I had been in search of, curious as to whether there was a precedent for the Flushing Remonstrance, or whether that particular set of early Long Islanders came up with the idea of writing a public letter to Peter Stuyvesant to protest his religious intolerance. (They did not come up with it. Remonstrances were a thing going back to King John of Magna Carta fame, according to the historian currently working the cash register at the Long Island City Trader Joe’s.)

Historians are everywhere, might be the moral of this post. Or, it pays to talk to strangers. Also to carry a business card.

Where the Streets Have No Name

My friend Lee once sent me a card that came back to her because she had misaddressed the envelope – nearly all the streets in Queens are numbered and many share a number, so that there is a 31st Avenue, Street, Road, and Drive within walking distance of me. All of the roadways once had names, of course, and they were all changed to a numbering system.

In 1898, Queens County decided to consolidate with Manhattan. While Brooklyn was an entire city when it joined Manhattan. Queens was a county of small villages, each with its own Broadway, its own Main, its own Elm.

A one-time official Queens Historian wrote: “By the 1920’s, in order to rationalize the maze of gridlets and ensure connectivity of the system, the Queens topographic bureau imposed an evenly spaced master grid over the entire borough. Streets began in the west in Long Island City and Avenues began in the north in Whitestone. . . named streets followed the contours of the land.”

That does not appease Lee, who still stings from the return of her greeting card. But it was Lee I thought of as I read through the minutes of the Board of Trustees of the Village of Astoria, 1839-1870 last week at the New York City Municipal Archives.

About a year ago, a man whom I don’t know and didn’t ask informed me on social media that the history of Astoria begins with Stephen Halsey. This unasked man is correct, I suppose. The history of the land does not begin with Halsey, but the history of Astoria does – it was incorporated by the New York state legislature in April 1839, and Halsey is the reason it is named Astoria. Halsey was a fur trader who was chummy with John Jacob Astor, which I suppose it was necessary to be if one was a fur trader at that time. But here I will defer to Rebecca Bratspies, a professor of environmental law at CUNY Law School and the author of Naming Gotham: The Villains, Rogues & Heroes Behind New York’s Place Names:

Stephen A. Halsey, founder of the Astoria neighborhood of New York, proposed naming the town after John Jacob Astor in the hopes that Astor would make a large donation to a young ladies’ seminary, which would also be named after him. Astor made the donation, but instead of the generous support Halsey had been hoping for, Astoria donated only $500 to the Astoria Institute . . . Astor himself never visited Astoria, even though he could see it from his country house on the other side of the East River.

Halsey is all over these early years, according to the minutes. I thought that minutes of a board of trustees would be dull reading, that I would be finished by lunch and on my way to the rest of my day off from the office. And they were dull reading – the building of walls, sidewalks, sewers, the maintenance of wells and pumps, the grading of streets, the placement of street lamps, the establishment of a fire department, the naming of a police constable. But they were also fascinating and kept me there until the archives closed, as I read the story of transformation from a bunch of farms and fledging factories being shaped into a town. Many of the early meetings were held in Halsey’s home.

And then I came upon the naming of the streets. Lee would rejoice!

“RESOLVED that a new street sixty feet wide to be designated as “Grand Street” shall be laid out and opened commencing at Welling Street and running in an easterly direction as far as the village limits extend along the line between the lands of C. B. Trafford and B R Stevens on one side and R M Blackwell – Buchanan & Gabriel Marc on the other side . . .”

Also established in these early minutes: Main Street, Flushing Avenue, Newtown Avenue, Sunswick Terrace, Greenock Street, Welling Street, Emerald Street, Linden Street, Woolsey Street and Remsen Street. Grand Avenue (not street) is now a subway stop, Remsen is 12th Street, Welling is Welling Court, Sunswick is a buried creek, and Newtown Avenue is Newtown Avenue. The rest would require some digging.

Certain prohibitions were also introduced: no person shall allow his livestock or fowl to wander at large, set off gunpowder or combustible material in public places, swim in the East River near the ferry slip or appear naked in a public place, or “raise or fly a kite in any street lane or alley within the village under the penalty of Five Dollars for every offence.”

I wondered what the deal was about flying a kite. There were no telephone lines to disrupt in 1848, and I doubt that there were all that many kites. I would have asked the friendly archivist, Marcia, but Marcia, who is from Flushing, had already hurried away to find a law dictionary when I asked her about the Flushing Remonstrance. I know about the Flushing Remonstrance; it was that word “remonstrance” that has bothered me. Were there other famous remonstrances?

There were remonstrances in the board of trustee minutes. A farmer remonstrated that the location of Grand Street would destroy some of his trees. The Hook and Ladder company remonstrated that the proposed Village Hall should not be in the firehouse.

More exciting to me than the evidence of other remonstrances was Marcia, the archivist, who responded to my questions with lots of information – files dug up, an Excel spreadsheet of other sources emailed to me, suggestions as to where other information might be housed. I hadn’t realized how parched I was for a sympathetic ear until she provided a gentle sprinkling of support. Writing is a lonely business at the best of time; writing researched nonfiction when one is not a journalist or historical can seem deranged.

“How’s your history of Astoria coming along?” smirked a work colleague at a recent lunch. Granted, this particular colleague can make the response to a mild “How are you?” sound scathing, but this dash of scorn reminded me to be careful who I tell (as my fellow writer but not relative Joan Frank once advised).

I know, I know. Be grateful for the librarians, the archivists, the other lonely historians, the kind stranger who gave me permission to quote from her PhD thesis on Mark di Suvero. Be grateful, and tell the naysayers (quietly, of course) to go fly a kite.

My Year in Reading 2022

I’m still working on expanding my reviewing, and was fortunate to land a new gig, so I’m looking forward to more in the coming year. I reviewed three books this year. They are therefore disqualified (and indicated in italics) from my top ten. I’ve also ordered several books written by friends but they may still be in the TBR pile, or not yet finished.

So, with the downtime I had at my disposal, excluding periodicals, and listening to podcasts excluded, here are the books:

For research

Typhoid Mary: An Urban Historical – Anthony Bourdain

Terrible Typhoid Mary – Susan Campbell Bartoletti

Deadly – Julie Chibbaro

The Lonely City – Olivia Laing

Open City – Teju Cole

Feral City – Jeremiah Moss

New York City Coffee: A Caffeinated History – Erin Meister

The Power Broker – Robert Caro

John Winthrop – Francis J. Bremer

Eye of the Sixties: Richard Bellamy of the Transformation of Modern Art – Judith E. Stein

The Architecture of Happiness – Alain de Botton

Mark di Suvero (edited by David R. Colleens, Nora R. Lawrence, Theresa Choi)

Work on the work-in-progress progresses, so I have started on readalikes. I’ve realized that there really is no way to tie in Typhoid Mary to the conceit of my book, but I have now read enough on her to consider myself an amateur expert. Halfway through the year I shifted my focus to Mark di Suvero, subscribed to Art in America, downloaded every article I could find at NYPL, and solicited a box of di Suvero family papers from the Smithsonian. And still I know so little that eking out 500 words took all I had.

All that said, The Power Broker occupied weeks and weeks of reading, even with using the audiobook. That book is long. I also saw the David Hare play, Straight Line Crazy, so I’m just about as up on Robert Moses as I am on Mary Mallon.

Reading resolution for this category: Continue with Mark di Suvero. Read other living Queens authors extensively for a workshop I hope to hold, with grants I hope to be granted.

Fiction

Five Tuesdays in Winter – Lily King

The Last True Poets of the Sea – Julia Drake

The Latecomer – Jean Hanff Korelitz

An Honest Living – Dwyer Murphy

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy – John Le Carre

Mercury Pictures Presents – Anthony Marra

Fellowship Point – Alice Elliott Dark

Natural History – Andrea Barrett

Shrines of Gaiety – Kate Atkinson

About Face – William Giraldi

Trust – Hernan Diaz

Trust Exercise – Susan Choi

I was surprised to see so few novels on my list, again, The Power Broker took up a lot of my summer. I was sad to leave the Lily King and the Kate Atkinson off my top ten list, but the memoirs below just nudged them out. The Marriage Portrait is in the queue.

Reading resolution for this category: See Queens authors, above. Otherwise, I will probably graze indiscriminately.

Memoir

Bluets – Maggie Nelson

H is for Hawk – Helen MacDonald

The Outrun – Amy Liptrot

Also a Poet – Ada Calhoun

The Lost Children of Mill Creek – Vivian Gibson

Easy Beauty – Chloe Cooper Jones

The Odd Woman and the City – Vivian Gornick

Reading resolution for this category: Don’t really have one? Crying in H Mart is waiting for me at the Astoria Library.

Essays

Animal Bodies – Suzanne Roberts

Orwell’s Roses – Rebecca Solnit

Like Love – Michele Morano

Hysterical – Elissa Bassist

Festival Days – Jo Ann Beard

All the Leavings – Laurie Easter

Bright Unbearable Reality – Anna Badkhen

Reading resolution for this category: I hope to review more in this category. I focus on collections published by indie and university presses.

Craft

Craft in the Real World – Matthew Salessas

A Swim in the Pond in the Rain – George Saunders

How to Write One Song – Jeff Tweedy

Reading resolution for this category: I am starting 2023 with a poetry workshop which has two rather daunting required texts, so, dare I say, I am good here?

Other nonfiction

Islands of Abandonment – Cal Flyn

The Strange Case of Dr. Couney – Dawn Raffel

Reading resolution for this category: I realize that this category is composed of writers with whom I took workshops in 2022, both of whom were super-kind and thoughtful.

Poetry

The Owl Was a Baker’s Daughter – Gillian Cummings

Long Rules – Nathaniel Perry

Reading resolution for this category: More, more, more.

Cozy old things and mysteries

Cheerfulness Sets In – Angela Thirlkill

The It Girl – Ruth Ware

The Madness of Crowds – Louise Penny

Dying to Tell – Robert Goddard

Reading resolution for this category: this is the “something fun to read” category. It defies resolve.

Happy reading in 2023 to all!

Mark di Suvero meets the Golden Gate Bridge

I haven’t been posting as often as I would like because I’ve been buried in research for my book about the history of the section of Astoria you can see from Chateau le Woof. The project was previously known as “Summer of the Dog Cafe” but it seems to have morphed into a book and it involves Hallett’s Cove, the former Sohmer piano factory where the dog cafe occupies part of the ground floor, and Socrates Sculpture Park, founded by Mark di Suvero, and Spacetime, the red warehouse which di Suvero uses as workspace. Teaching myself about the Puritans, the history of pianos in New York City, and the rise of public art and then trying to turn it into prose has been a slow process! It took me forever, it seems, for example, to come up with the opening paragraphs of the chapter on Mark di Suvero, but here they are for your appraisal.

In 1941, a family left China to sail across the Pacific, fleeing a war that would not be fled. Although they had been living in China for years, the family was Italian. The father, a naval attaché, was Venetian, as was the mother, a former Countess. With them were their four children, each of whom faced radiant destinies: an activist lawyer who would establish a law school, an art historian, a poet and a world-renowned artist.

Let’s envision the future artist, nine years old, on the deck on the S.S. President Cleveland. His hands, wet with ocean mist, grip the railings as the Cleveland navigates from the great Pacific into San Francisco Bay. Here it is at last: America. America, named for an Italian explorer, just as he was, Marco Polo di Suvero. Perhaps he claps with excitement. We focus on his hands because his early public work will be of hands, clutching, opening, pointing.

Days of gazing at the endless blue of ocean and sky are suddenly broken by the terrible bright splendor of this span of steel, stretching across the bay for a mile, so long that the bridge never stops being painted. The last brush stroke on the south end in San Francisco serves as a signal to commence the next coat on the north end in Marin County. The color of the paint is International Orange. It flares into the eyes of the blue-blinded boy, himself an international fruit, an Italian raised in China entering America under a suspension bridge with towers so tall that they routinely disappear into clouds as though seeking the release of heaven. The bridge was begun the same year he was born, but it is only four years old, like a younger brother.

International Orange is a reddish orange firmly associated with the Golden Gate Bridge. But it is abundant on earth. We find it in the clay soil of Georgia, in the heart of a peach, in marigolds and goldfish, butterflies and autumn leaves, Irish setters and redheads. We find it in flames. But the color really belongs to the sky, in the grace of the sun rising and setting.

But who could imagine dousing a monument of steel with such a fierce, celestial color. The future sculptor Mark di Suvero, first encountering America, was too young to formulate such questions. He was just a boy, and what he most likely thought was “Golly, look at that!” or, more likely, “Che meraviglia!” But that encounter, and that thought, would direct the rest of his life, shape the course of the lives of dozens if not hundreds of other artists, and heavily influence the landscape of a certain stretch of Vernon Boulevard in Astoria, New York.

Recent Comments