Saorsie the Shepherdess

Yesterday, I took the train north to begin a weeklong stay at the Hudson Valley Writers Residency. For my train reading, I brought along the book Learning to Look at Sculpture because I have been searching for a primer on sculpture in order to grow smarter for the Mark di Suvero sections of the dog café book. (I have decided on the title We Live in Hidden Cities, but its every day title is “the dog café book” or, as a texting friend typo-ed to me recently, “dog cage.”) I didn’t learn much about sculpture beyond “it is an art form with which we share space.” I fell into conversation with my Amtrak seatmate, a handsome young woman in the vein of Julia Stiles.

Readers are reminded that the description of this website contains the phrase “champion of the chance encounter.”

My seatmate was on the last leg of her trip home from Scotland, where she had gone on an Outlander tour. (“Lallybroch!” “The Battle of Culloden!”) I am fluent enough in Outlander (the show, not the books) and then we branched into various things Scottish. I told her that it is my ambition to do a residency at Hawthornden Castle outside Edinburgh, and that I was on my way to a residency for the week. What am I working on? The history of one block in my neighborhood. She told me that she was majoring in history and had recently written a paper about how women’s history, so often obscured from the written record, can often be found in textiles. She attends SUNY Empire, an online program, which enables her to help out on the family farm, further upstate, where her family raises livestock, mainly sheep.

It struck me that leaving a sheep farm to vacation in Scotland was something of a busman’s holiday. I didn’t say this to her because she is 20-something and I doubted that she would know the term.

Instead, I said, “So you’re a shepherdess.”

Her mother is writing an historical novel about the family farm. I am all for historical novels (having written one and having one in a state of benign abandonment) and read over the summer Ben Shattuck’s The History of Sound, which a poetry professor at MY SUNY program told us was a collection of short stories written in a form called hook-and-chain, a form popularized in New England in the 19th century, which follows the pattern a bb cc dd ee ff a. I recommended this book to the shepherdess, along with Andrea Barrett, who I recommend to everyone. She didn’t write any of this down – I was a stranger on a train bothering a young woman who’d flown to JFK from Scotland, then taken the Long Island Rail Road to Penn Station to get an Amtrak to take her upstate to her farm. But maybe she will see this.

Champion of the chance encounter.

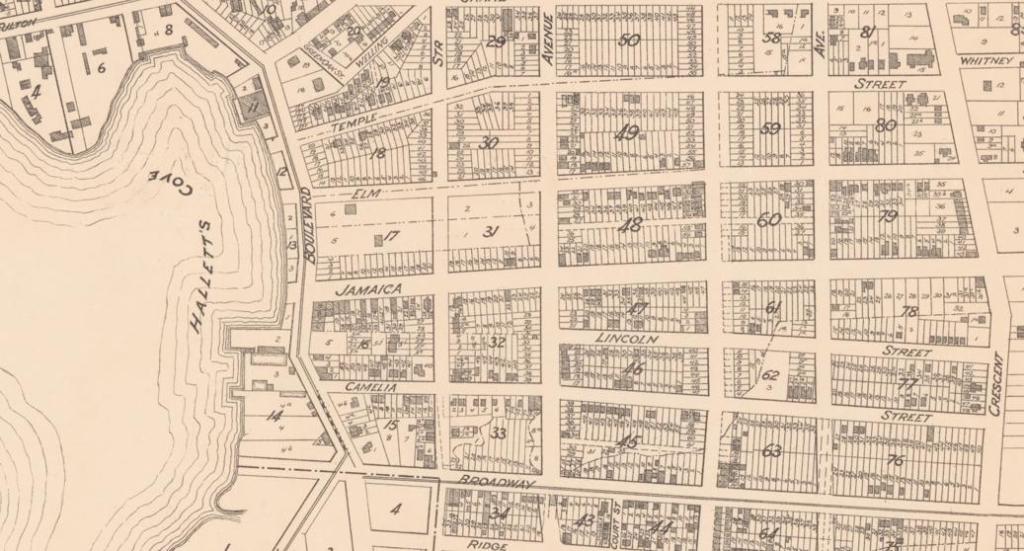

Earlier this summer, I visited the Queens Historical Society to see if I could get an answer to the question, “What was that parcel of land that juts into the East River between the time it was Stephen Halsey’s house and the time it was turned into NYCHA Housing?” I looked at maps and chatted with Jason Antos, the historian on site. Then since I was on the 7 line anyway, I took the 7 train to the Trader Joe’s in Long Island City, where I wound up chatting with the cashier as she checked me out. She too is a history student and had written a paper on the history of the Gowanus Canal. She later read this very blog and sent me a brief history of remonstrances, which I had been in search of, curious as to whether there was a precedent for the Flushing Remonstrance, or whether that particular set of early Long Islanders came up with the idea of writing a public letter to Peter Stuyvesant to protest his religious intolerance. (They did not come up with it. Remonstrances were a thing going back to King John of Magna Carta fame, according to the historian currently working the cash register at the Long Island City Trader Joe’s.)

Historians are everywhere, might be the moral of this post. Or, it pays to talk to strangers. Also to carry a business card.

Where the Streets Have No Name

My friend Lee once sent me a card that came back to her because she had misaddressed the envelope – nearly all the streets in Queens are numbered and many share a number, so that there is a 31st Avenue, Street, Road, and Drive within walking distance of me. All of the roadways once had names, of course, and they were all changed to a numbering system.

In 1898, Queens County decided to consolidate with Manhattan. While Brooklyn was an entire city when it joined Manhattan. Queens was a county of small villages, each with its own Broadway, its own Main, its own Elm.

A one-time official Queens Historian wrote: “By the 1920’s, in order to rationalize the maze of gridlets and ensure connectivity of the system, the Queens topographic bureau imposed an evenly spaced master grid over the entire borough. Streets began in the west in Long Island City and Avenues began in the north in Whitestone. . . named streets followed the contours of the land.”

That does not appease Lee, who still stings from the return of her greeting card. But it was Lee I thought of as I read through the minutes of the Board of Trustees of the Village of Astoria, 1839-1870 last week at the New York City Municipal Archives.

About a year ago, a man whom I don’t know and didn’t ask informed me on social media that the history of Astoria begins with Stephen Halsey. This unasked man is correct, I suppose. The history of the land does not begin with Halsey, but the history of Astoria does – it was incorporated by the New York state legislature in April 1839, and Halsey is the reason it is named Astoria. Halsey was a fur trader who was chummy with John Jacob Astor, which I suppose it was necessary to be if one was a fur trader at that time. But here I will defer to Rebecca Bratspies, a professor of environmental law at CUNY Law School and the author of Naming Gotham: The Villains, Rogues & Heroes Behind New York’s Place Names:

Stephen A. Halsey, founder of the Astoria neighborhood of New York, proposed naming the town after John Jacob Astor in the hopes that Astor would make a large donation to a young ladies’ seminary, which would also be named after him. Astor made the donation, but instead of the generous support Halsey had been hoping for, Astoria donated only $500 to the Astoria Institute . . . Astor himself never visited Astoria, even though he could see it from his country house on the other side of the East River.

Halsey is all over these early years, according to the minutes. I thought that minutes of a board of trustees would be dull reading, that I would be finished by lunch and on my way to the rest of my day off from the office. And they were dull reading – the building of walls, sidewalks, sewers, the maintenance of wells and pumps, the grading of streets, the placement of street lamps, the establishment of a fire department, the naming of a police constable. But they were also fascinating and kept me there until the archives closed, as I read the story of transformation from a bunch of farms and fledging factories being shaped into a town. Many of the early meetings were held in Halsey’s home.

And then I came upon the naming of the streets. Lee would rejoice!

“RESOLVED that a new street sixty feet wide to be designated as “Grand Street” shall be laid out and opened commencing at Welling Street and running in an easterly direction as far as the village limits extend along the line between the lands of C. B. Trafford and B R Stevens on one side and R M Blackwell – Buchanan & Gabriel Marc on the other side . . .”

Also established in these early minutes: Main Street, Flushing Avenue, Newtown Avenue, Sunswick Terrace, Greenock Street, Welling Street, Emerald Street, Linden Street, Woolsey Street and Remsen Street. Grand Avenue (not street) is now a subway stop, Remsen is 12th Street, Welling is Welling Court, Sunswick is a buried creek, and Newtown Avenue is Newtown Avenue. The rest would require some digging.

Certain prohibitions were also introduced: no person shall allow his livestock or fowl to wander at large, set off gunpowder or combustible material in public places, swim in the East River near the ferry slip or appear naked in a public place, or “raise or fly a kite in any street lane or alley within the village under the penalty of Five Dollars for every offence.”

I wondered what the deal was about flying a kite. There were no telephone lines to disrupt in 1848, and I doubt that there were all that many kites. I would have asked the friendly archivist, Marcia, but Marcia, who is from Flushing, had already hurried away to find a law dictionary when I asked her about the Flushing Remonstrance. I know about the Flushing Remonstrance; it was that word “remonstrance” that has bothered me. Were there other famous remonstrances?

There were remonstrances in the board of trustee minutes. A farmer remonstrated that the location of Grand Street would destroy some of his trees. The Hook and Ladder company remonstrated that the proposed Village Hall should not be in the firehouse.

More exciting to me than the evidence of other remonstrances was Marcia, the archivist, who responded to my questions with lots of information – files dug up, an Excel spreadsheet of other sources emailed to me, suggestions as to where other information might be housed. I hadn’t realized how parched I was for a sympathetic ear until she provided a gentle sprinkling of support. Writing is a lonely business at the best of time; writing researched nonfiction when one is not a journalist or historical can seem deranged.

“How’s your history of Astoria coming along?” smirked a work colleague at a recent lunch. Granted, this particular colleague can make the response to a mild “How are you?” sound scathing, but this dash of scorn reminded me to be careful who I tell (as my fellow writer but not relative Joan Frank once advised).

I know, I know. Be grateful for the librarians, the archivists, the other lonely historians, the kind stranger who gave me permission to quote from her PhD thesis on Mark di Suvero. Be grateful, and tell the naysayers (quietly, of course) to go fly a kite.

Recent Comments