A letter to my Canadian publisher about last night’s World Series game

First of all, no. No, games do not usually last that long. In fact, they never last that long. An 18-inning game is in fact two games. This is unprecedented — a word sadly overused in our beleaguered times — but it is. I am sure you didn’t stay up to watch. At 11:24 my time, you texted to me: “These innings take forever. I am not even watching, but it is hard to go to sleep when it is tied.” I was already asleep, and the ding on my phone woke me up. It is impossible to watch the game in the U.S. without a subscription to Fox Sports, and I do not have one, for various reasons.

Later in the night, I woke up. Not at three — “In a real dark night of the soul it is always three o’clock in the morning,” wrote F. Scott Fitzgerald — so say it was two o’clock in the morning, when I checked my phone (sleep experts say you should not do this, but perhaps this is why I am so very very tired) and the game was still tied.

“Nobody on, nobody out,” I mumbled to nobody. I rolled over and went back to sleep. Perhaps the empty room appreciated the literary reference to my long-unpublished novel, Nobody On, Nobody Out, my second novel, and the first novel for which I had a literary agent.

So my second novel was what should have been my first novel, an autobiographical coming-of-age. (Instead, my first novel, Cooder Cutlas, was a rock and roll on the Jersey Shore story, which I believe if I’m not mistaken is a story quite in vogue this week?). So, Nobody On, Nobody Out follows a weekend in the life of a teenaged girl in a motherless, baseball-obsessed family. Our heroine, Alison, an aspiring sportswriter, is playing Helena in her school’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream while also following the progress of her team, the St. Louis Browns, in the American League Championship Series playoffs. (The St. Louis Browns were a real team who moved to Baltimore in 1953 and became the Baltimore Orioles. Similarly, the Brooklyn Dodgers moved to Los Angeles in 1958. You do not need to know this, except that it is something that can be known.)

At the time, the American League had a rule that a game must end at midnight. Because of that, and various rain delays, the game in the novel lasts an entire weekend. I wrote this novel on a typewriter in my sister’s spare bedroom in Philadelphia and when it was finished I mailed the paper manuscript to an agent at the William Morris Agency who had expressed interest in my writing career. He did this by placing his hand on the manuscript for Cooder Cutlas and intoning, like a bailiff in a courtroom, “I think this is a good book.” (Dramatic pause.) “I don’t think this is the best book you will ever write.”

He said the same thing about Nobody On, Nobody Out, eerily predicting the long and thankless road my writing career would take. I did get an another agent for that novel, however, and over the course of a year gathered a soft, leafy pile of rejection letters, full of praise but ultimately rejecting the work as “too YA.” (This was well before YA became a desirable thing — it was still something of a publishing ghetto at the time.)

Nobody On, Nobody Out, anyway, Netta, was inspired by a 1974 game between the New York Mets and my beloved St. Louis Cardinals which lasted 25 innings and lasted seven hours and four minutes (don’t be impressed — I had to google this.) It set records in various ways. I did not stay up to listen to it; it was a school night. But my father did. Of course my father did. We were awakened from time to time by the sound of his hand slamming against the counter when a play did not go as he wished. This was the soundtrack to my childhood.

So no, Netta, games do not always go on that long. But yes, they are always that slow. When I say “slow,” I mean leisurely. This is why baseball is the preferred sport of poets. Baseball allows you time to think. Not the kick-kick-run-run of soccer (or “football”) or the war-game-meets-planning-committee bluster of American football. It is a strategic. It is a duel. It is bucolic, going back to agrarian roots.

“It is summer,” wrote William Carlos Williams. “It is the solstice/the crowd is/cheering, the crowd is laughing/in detail/permanently, seriously/without thought.”

Another poet, Robert Frost, wrote “Poets are like baseball pitchers. Both have their moments. The intervals are the tough things.”

The intervals are the tough things, don’t you think? We are in a tough interval as a national here down south, and I think those of us who are not enamored by the frenzy of other sports find solace in the leisurely pace. It reminds me of Jordan Baker’s line in The Great Gatsby: “I like large parties. They’re so intimate. At small parties there isn’t any privacy.” Similarly, baseball is intimate, and the busy sports don’t afford you any privacy, any time at all to spend with your thoughts.

And there is nothing more beautiful in the sporting world than Dodger Stadium as the sun goes down.

Where the Streets Have No Name

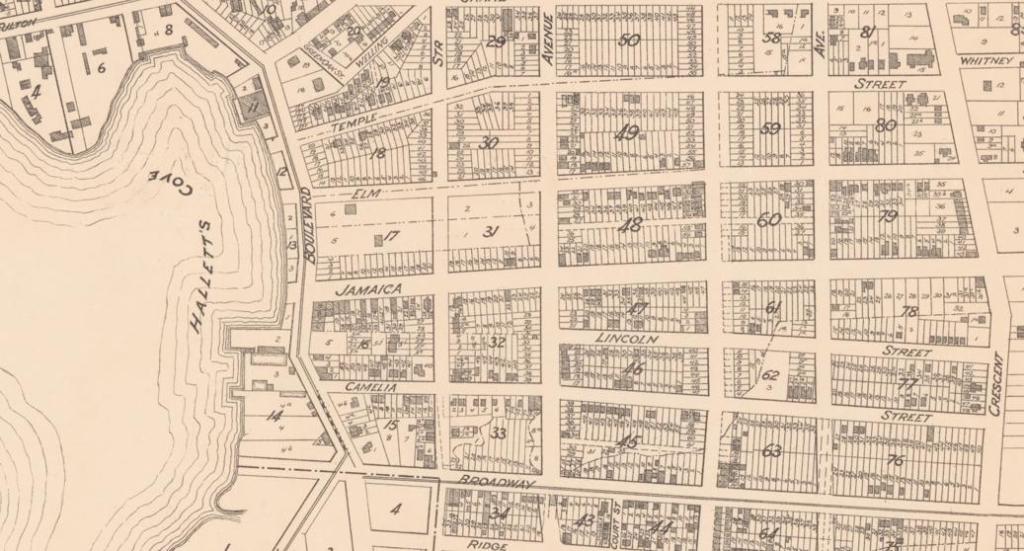

My friend Lee once sent me a card that came back to her because she had misaddressed the envelope – nearly all the streets in Queens are numbered and many share a number, so that there is a 31st Avenue, Street, Road, and Drive within walking distance of me. All of the roadways once had names, of course, and they were all changed to a numbering system.

In 1898, Queens County decided to consolidate with Manhattan. While Brooklyn was an entire city when it joined Manhattan. Queens was a county of small villages, each with its own Broadway, its own Main, its own Elm.

A one-time official Queens Historian wrote: “By the 1920’s, in order to rationalize the maze of gridlets and ensure connectivity of the system, the Queens topographic bureau imposed an evenly spaced master grid over the entire borough. Streets began in the west in Long Island City and Avenues began in the north in Whitestone. . . named streets followed the contours of the land.”

That does not appease Lee, who still stings from the return of her greeting card. But it was Lee I thought of as I read through the minutes of the Board of Trustees of the Village of Astoria, 1839-1870 last week at the New York City Municipal Archives.

About a year ago, a man whom I don’t know and didn’t ask informed me on social media that the history of Astoria begins with Stephen Halsey. This unasked man is correct, I suppose. The history of the land does not begin with Halsey, but the history of Astoria does – it was incorporated by the New York state legislature in April 1839, and Halsey is the reason it is named Astoria. Halsey was a fur trader who was chummy with John Jacob Astor, which I suppose it was necessary to be if one was a fur trader at that time. But here I will defer to Rebecca Bratspies, a professor of environmental law at CUNY Law School and the author of Naming Gotham: The Villains, Rogues & Heroes Behind New York’s Place Names:

Stephen A. Halsey, founder of the Astoria neighborhood of New York, proposed naming the town after John Jacob Astor in the hopes that Astor would make a large donation to a young ladies’ seminary, which would also be named after him. Astor made the donation, but instead of the generous support Halsey had been hoping for, Astoria donated only $500 to the Astoria Institute . . . Astor himself never visited Astoria, even though he could see it from his country house on the other side of the East River.

Halsey is all over these early years, according to the minutes. I thought that minutes of a board of trustees would be dull reading, that I would be finished by lunch and on my way to the rest of my day off from the office. And they were dull reading – the building of walls, sidewalks, sewers, the maintenance of wells and pumps, the grading of streets, the placement of street lamps, the establishment of a fire department, the naming of a police constable. But they were also fascinating and kept me there until the archives closed, as I read the story of transformation from a bunch of farms and fledging factories being shaped into a town. Many of the early meetings were held in Halsey’s home.

And then I came upon the naming of the streets. Lee would rejoice!

“RESOLVED that a new street sixty feet wide to be designated as “Grand Street” shall be laid out and opened commencing at Welling Street and running in an easterly direction as far as the village limits extend along the line between the lands of C. B. Trafford and B R Stevens on one side and R M Blackwell – Buchanan & Gabriel Marc on the other side . . .”

Also established in these early minutes: Main Street, Flushing Avenue, Newtown Avenue, Sunswick Terrace, Greenock Street, Welling Street, Emerald Street, Linden Street, Woolsey Street and Remsen Street. Grand Avenue (not street) is now a subway stop, Remsen is 12th Street, Welling is Welling Court, Sunswick is a buried creek, and Newtown Avenue is Newtown Avenue. The rest would require some digging.

Certain prohibitions were also introduced: no person shall allow his livestock or fowl to wander at large, set off gunpowder or combustible material in public places, swim in the East River near the ferry slip or appear naked in a public place, or “raise or fly a kite in any street lane or alley within the village under the penalty of Five Dollars for every offence.”

I wondered what the deal was about flying a kite. There were no telephone lines to disrupt in 1848, and I doubt that there were all that many kites. I would have asked the friendly archivist, Marcia, but Marcia, who is from Flushing, had already hurried away to find a law dictionary when I asked her about the Flushing Remonstrance. I know about the Flushing Remonstrance; it was that word “remonstrance” that has bothered me. Were there other famous remonstrances?

There were remonstrances in the board of trustee minutes. A farmer remonstrated that the location of Grand Street would destroy some of his trees. The Hook and Ladder company remonstrated that the proposed Village Hall should not be in the firehouse.

More exciting to me than the evidence of other remonstrances was Marcia, the archivist, who responded to my questions with lots of information – files dug up, an Excel spreadsheet of other sources emailed to me, suggestions as to where other information might be housed. I hadn’t realized how parched I was for a sympathetic ear until she provided a gentle sprinkling of support. Writing is a lonely business at the best of time; writing researched nonfiction when one is not a journalist or historical can seem deranged.

“How’s your history of Astoria coming along?” smirked a work colleague at a recent lunch. Granted, this particular colleague can make the response to a mild “How are you?” sound scathing, but this dash of scorn reminded me to be careful who I tell (as my fellow writer but not relative Joan Frank once advised).

I know, I know. Be grateful for the librarians, the archivists, the other lonely historians, the kind stranger who gave me permission to quote from her PhD thesis on Mark di Suvero. Be grateful, and tell the naysayers (quietly, of course) to go fly a kite.

Basic Grandeur

In 2023, my New Year’s resolution was to take my lifelong flirtation with poetry, which I have written about elsewhere, into the next step. I needed to take a poetry writing class. I must have found my first class on Facebook. It was run by a nice woman who used to run a writing group in St. Louis, and much of the group were her St. Louis former cohorts. The class got me over the first hurdle, which was to write poems and share them with strangers. But it was too easy, so my next class was with the 92nd St. Y with an instructor who I won’t name because I found both her and her approach very chilly.

By now I was Goldilocks – too easy, too hard – so I submitted a few poems again to the 92nd St Y, to Advanced Poetry with Maya C. Popa because I wanted to work with her. I never expected to be accepted. But I was. And she was just right. I typed “write” the first time – Freudian, perhaps, but not a slip.

Then I went to podcasts. The Slowdown is a podcast hosted currently by Major Jackson, formerly by Ada Limon, which begins with a rumination from the host on anything going on in his/her/their life, followed by a poem. These podcasts are pleasant, but I need to hear a poem more than once. Which is what happens on Poetry Unbound, hosted by Padraig O Tuama, who reads the poem, reflects on it at length, and then reads it again. The New Yorker Poetry podcast hosted by Kevin Young is also on heavy rotation in my podcast feed. (Do people still say “heavy rotation”?)

Back to classes: I’ve had several more with Maya C. Popa, but I am a flawed student. I am conflicted about sharing my poetic work (“work”!), I don’t know how to revise, I don’t know some of the terminology my classmates are throwing around , sometimes I freak out and bail, and this is a run-on sentence. But now I’m hooked.

Many years ago, for April is Poetry Month, I posted a fragment of a poem, along with the title and name of the poet, on my Facebook page. I decided this year to do this again, with the proviso that I only highlight work by living poets. (Someone forgot to tell me that Eavon Boland had died.)

I front-loaded this endeavor by stockpiling two weeks’ worth of snippets of poems. I started with poets I “knew,” in the sense that I had met them at a writer’s conference, or heard them read, or generally been in a place where for a pulse of a moment (poetic?), we breathed the same air. So this included Patricia Smith, Kathleen Graber, A. Van Jordan and Jon Riccio, all of whom I encountered at Vermont College of Fine Arts. They were followed by Poets of Queens – Jared Harel, Jared Beloff and Oleana Jennings. And then people I’d encountered in magazines, or whose books I’d purchased.

The selection of the day was not dictated by any circumstances of the day. For example, in the past , I have chosen a poem reflecting my sister’s interests on for her April birthday. And many worthy poems were not included simply because I could not find an engaging snippet that could be easily extracted from the larger work.

As they say in baseball (also an April event), there’s always next year.

Kicking and Giving

I have now completed the second week of my fully-remote life. My previous job had a one-day-a-week-in-the-office policy for those of us in IT. For some reason, although I was in the research library, I was umbrellaed under IT. (My inability to master layout in the upgraded version of WordPress tells you allyou need to know about me working in an IT department.) When I asked my boss why the library was IT, his reply was “Gotta put us somewhere,” which effectively sums up what led me to leave that job — the lack of engagement, the listless dismissal of legitimate inquiry. The loneliness. In my new role, I am back to research umbrellaed under business development, which sets the world right again, but it is fully remote. Although this is only the difference of one day a week, it is a mindset which sets the mind reeling. To ward off the loneliness, I have committed myself to Pilates and knitting, two things at which I will be terrible for the foreseeable future, but both of which are within walking distance (there are two knitting groups that meet at different bars. I know one stitch.)

And then daily, I take long walks and write in a coffee shop. There is Chateau le Woof, of course, but nearer to home, so that I can get a walk-and-write in before logging on to work, there are three cafes: Under Pressure, Madame Sou Sou and Astoria Coffee. Under Pressure has a high-tech, sleek European vibe, a business-district-transformed-from-its-industrial-past-near-a-branch-of-the-Guggenheim-and-a-W-hotel kind of Europe. Madame Sou Sou has an Old Town European vibe, a cafe-on-a-narrow-street-full-of-quaint-shops-that-are-always-closed-recommended-by-the-landlady-at-your-AirBnB kind of Europe. Astoria Coffee has no European vibe at all. Extremely small even by NYC standards, it is resolutely Astorian, patriotically displaying on its limited wall space art photos of Astoria taken by local photographers.

But it is at Under Pressure where I set my first scene.

Despite its only-in-town-for-fashion-week interior, its clientele is mainly Greek and mainly working class. There is outdoor seating where you can watch the elevated train go by, or watch people line up to order gyros from the Greek on the Street food cart, or watch a traffic cop strolling down the avenue looking for victims. Under Pressure’s employees are Greek,and if their highly amused reactions at my attempts to greet them in their native tongue are any indication, no amount of living in Astoria will help my accent. I was sitting outside with my coffee and my notebook, earbuds in but podcast off. Three men were seated behind me, Queens natives by their accent, contractors by their conversation.

Guy on phone: “Look, I told you I needed you to have the bathroom done by the end of the week . . . that ain’t my problem. . . do what you gotta do. Come in early, stay late, get it done.”

I returned my focus to my to-do list, writing a list of what needed to be written, which is about all the writing I’ve done during the job transition. I heard a voice say “She’s not friendly,” and a moment later a man walked by, his Shiba Inu on a leash trotting alongside him.

Warning: the language below is foul but accurately recorded.

The first man said, “What the fuck! Not friendly!”

The second man said, “The fuck bring it out in public for if it’s not friendly.”

The third man said, “I’ll kick that fucking dog.”

At this point, I pulled out my earbuds and turned around.

The first man at least looked abashed. “Didn’t think you could hear with those things in.”

I explained that the Shiba Inu is a loyal-owner breed, until a few exchanges compelled me to stop. The second man muttered “Shiba Inu,” like it was a new obscenity to welcome into his lexicon. The dog kicker said “I got a pit bull. He don’t like people, I don’t take him outside.”

I held up my palm in the universarl signal for “I will now exit this conversation” that in this case meant “I have no wish to play the extra in a community theater production of Goodfellas.”

Later in the week, I sat at Madame Sou Sou with my coffee and notebook writing about the Under Pressure encounter when I found myself within earshot of a coffee date, a young American man, a young European woman, awkward (“I like your shoes”) and endearing. He explained that he would spend the next day at a “Friendsgiving” and I happened to lift my head in time to see her tumble the phrase in her mind, extrapolating from her familiarity with “Thanksgiving” as a North American holiday to ask “What is a ‘giving’?” .

As he explained, I entertained the idea of a “giving,” a celebration where people gather out of choice, not obligation, not freighted with travel rushes and mandatory dishes, expectations, disappointments, grudges, too much stuffing, stuffing of everything.

So, my friends, I wish you a good giving. (But no kicking.)

Is there a place that means a lot to you?

Yesterday I conducted the second of my readings/workshop at Chateau le Woof. It was, New York-famously, the seventh consecutive Saturday of rain, so my expectations of attendance were low. Who would venture through more sogginess to attend a reading of a work-in-progress advertised by an admittedly cute but somewhat vague flyer?

Yet, people came. One was my friend Tess, who I met at the VCFA conference last August, her friend Hannah, two kind neighbors, and a woman who I met in the most interesting manner. This work-in-progress has been a work-in-progress, as I shift and distill its focus from so many tantalizing possibilities. Initially, I began visiting the Chateau le Woof (aka “the dog cafe”) just after the vaccines were rolling out, in the late spring of 2021. I was privileged enough to be able to work from home, but also stir-crazy enough to need to be somewhere other than my home, with other people, yet not indoors. The dog cafe, an indoor-outdoor space, was perfect. I reflected on how we had quarantined ourselves during this pandemic, but during previous epidemics, New York City had quarantined the sick on the islands surrounding Astoria — Roosevelt Island, previously known as Welfare Island and before that Blackwell’s Island, had been home to hospitals, jails, poorhouses and a notorious lunatic asylum. North Brother Island had been home to a tuberculosis hospital. Hart Island was a potter’s field begun after the Civil War and in active use during the height of the pandemic, where graves were dug for the unclaimed dead by the unhappy residents of Riker’s Island.

I still have a draft of that chapter — “Exiles of the Smaller Isles” — but realized I could not use the background research I’d done on Typhoid Mary. She was sentenced to life on North Brother Island, not in the tuberculosis hospital (where she worked as a lab assistant) but in her own small cottage from which, in the imagination of novelist Mary Beth Keane in her novel FEVER, Mary falls asleep to the sound of the rushing currents of the Hellgate, a rapid, still-dangerous stretch of the East River between Ward Island and Astoria. FEVER is an excellent if bleak novel detailing the options of an unmarried immigrant woman at the end of the 19th century. At one point, the caretaker on North Brother Island points out to Mary that her life in her tiny cottage with her little dog, however lonely and powerless, is still much better than some have it.

My favorite of these books was TYPHOID MARY: AN URBAN HISTORICAL which was surprisingly hard to get a hold of, considering its author, Anthony Bourdain. It is top-of-the-game Bourdain, scathing and snappy, but I had to get it on Kindle, because it may be out of print. So it was not among the stack of books I took to the closest Little Free Library. I deposited them and at the same time was delighted to see that the small wooden box held a copy of UNCOMMON GROUNDS, a history of coffee, which was on my list of books I needed for research.

Another woman browsing the Little Free Library eagerly grabbed ALL the Typhoid Mary books, with such enthusiasm that I tilted my head at her. She explained that she was an epidemiologist with the New York City Department of Health.

“So . . . how was your pandemic?” I asked.

She attended the reading, along with her friend, another epidemiologist.

I started keeping this blog such a long time ago that I forget my own logline sometimes, which ends with “champion of the chance encounter.” This was one, if ever there was one.

On Keeping a Notebook

“Keepers of private notebooks are a different breed altogether, lonely and resistant rearrangers of things, anxious malcontents, children afflicted apparently at birth with some presentiment of loss.”

So writes Joan Didion in her essay “On Keeping a Notebook,” which seems to be frequently assigned in graduate-level English classes, so that I was able to snatch this quote off the internet as soon as I determined this morning to write about notebooks. Apparently, when she wrote this piece, keeping a notebook was rare (although no, it wasn’t), or the distinction between notebook and diary had to be made explicit. As far as this quote goes, I say: speak for yourself, Joan.

But to say “speak for yourself,” to Joan Didion is so much a tautology than I can scarcely think of another example, unless it were, say, “Spell it out, Sesame Street.”

I keep a notebook and admit that I am lonely and a malcontent (perhaps another tautology?) but I dispute “resistant rearranger of things” because I’m not sure what it means, and “presentiment of loss” as a child because, in the case of my childhood, it was not a presentiment, but an observation.

I have been thinking lately about notebooks, not only because they are the only things I hoard – I have come to terms with that – and not only because I recently, after several stressful weeks at the day job, rewarded myself by breaking out the fanciest notebook in my hall closet collection.

It is this one, a Japanese notebook from the bookstore Kinokuniya across from Bryant Park. I would say more about the brand but alas, the product information is in Japanese. This notebook weighs too much and costs too much but otherwise, it fits all the criteria for an ideal notebook. It does not impede the flow of writing. It lies flat. The paper is soft enough to be pleasant to the hand resting on it. (The paper in this Kinokuniya notebook is the softest thing I have ever felt that is not fabric, skin or fur.) It is quick to seize ink. It resists a tear (in both senses.) And the notebook itself is sturdy enough to survive the apparent turmoil of the life inside of my handbag.

In the Poetry Folio newsletter released today from Atticus Review that landed in my inbox this morning, poet Michael Meyerhofer reminisced about his favorite notebooks to keep, the free pocket-sized notebooks issued from the bank in the small farming town he grew up in – “twenty or thirty blank pages about as long as your index finger.” He took a stack of them with him to college and maintains an appreciation for them even as electronic note-taking has gradually replaced them. He writes that sometimes all we can do is “fill these tiny little pages while we can.”

A few weeks back, I attended a members-only night at the Whitney Museum, where I learned that the Whitney has a great many members. The Whitney is in its final weeks of an exhibit devoted to Edward Hopper. I learned in the gift shop that Edward Hopper used to roam the city armed with notebooks purchased from the five-and-dime. Edward Hopper! Now here’s a “lonely and resistant rearranger of things”! He found, in the clamor of a relentlessly bustling metropolis, images of solitary and faceless office workers, viewed through plate-glass windows, caught in a melancholy stillness. We might envision Hopper, passing such a scene on the elevated train, which he reportedly rode sometimes all night, grabbing his dimestore notebook to rough out a future painting.

Or we might envision, as a savvier and presumably less melancholy and presentiment-of-loss-afflicted merchandising executive did, reproducing these Woolworth notebooks used by Hopper, with their old-timey typeface announcing their old-fashioned titles – “Ledger,” “Cash,” “Journal” – to sell in the Whitney gift shop for $18.50.

I’m not here to decry the cost. My Kinokuniya notebook — with its more daunting title “Life” — cost even more than that. But I am wondering what is the appeal of the reproduction of a once-cheap, utilitarian notebook. Why has such an object been elevated to the status of a museum gift shop item? The notebook was not designed by Hopper, or touched by Hopper but only implicitly endorsed by Hopper. And even that implicit endorsement is a long stretch. He probably used those notebooks because they were handy. He was a broke artist. He was more interested in the message than the medium.

I don’t know what a buyer of one of these notebooks hopes to be purchasing. Perhaps she just thinks it’s cute. Who am I to judge? (Okay, I’m judging a bit.) But it took me years of this notebook and that one, the here-you-like-to-write gifts and the singular bliss to be found in day job supply closets, to realize what suited notebooks suited me and why. The imperative is that it does not impede the flow of writing. So I have smaller notebooks, pocket-sized ones, old-fashioned reporter notebooks that can fit in one hand while you use the other to write, lightweight notebooks for a weekend trip, steno pads bought at office supply stores if I forgot to bring anything and yes, of course, tiny free pamphlets.

I suppose I would encourage anyone who hopes to channel inspiration by purchasing a reproduction of the kind of notebook Hopper favored to instead find her own notebook. As Cavafy encouraged his readers to find their own Ithaka.

Ithaka gave you the marvelous journey.

Without her you wouldn’t have set out.

She has nothing left to give you now.

But if you were wise, on that journey, you kept a notebook.

My Year in Reading 2022

I’m still working on expanding my reviewing, and was fortunate to land a new gig, so I’m looking forward to more in the coming year. I reviewed three books this year. They are therefore disqualified (and indicated in italics) from my top ten. I’ve also ordered several books written by friends but they may still be in the TBR pile, or not yet finished.

So, with the downtime I had at my disposal, excluding periodicals, and listening to podcasts excluded, here are the books:

For research

Typhoid Mary: An Urban Historical – Anthony Bourdain

Terrible Typhoid Mary – Susan Campbell Bartoletti

Deadly – Julie Chibbaro

The Lonely City – Olivia Laing

Open City – Teju Cole

Feral City – Jeremiah Moss

New York City Coffee: A Caffeinated History – Erin Meister

The Power Broker – Robert Caro

John Winthrop – Francis J. Bremer

Eye of the Sixties: Richard Bellamy of the Transformation of Modern Art – Judith E. Stein

The Architecture of Happiness – Alain de Botton

Mark di Suvero (edited by David R. Colleens, Nora R. Lawrence, Theresa Choi)

Work on the work-in-progress progresses, so I have started on readalikes. I’ve realized that there really is no way to tie in Typhoid Mary to the conceit of my book, but I have now read enough on her to consider myself an amateur expert. Halfway through the year I shifted my focus to Mark di Suvero, subscribed to Art in America, downloaded every article I could find at NYPL, and solicited a box of di Suvero family papers from the Smithsonian. And still I know so little that eking out 500 words took all I had.

All that said, The Power Broker occupied weeks and weeks of reading, even with using the audiobook. That book is long. I also saw the David Hare play, Straight Line Crazy, so I’m just about as up on Robert Moses as I am on Mary Mallon.

Reading resolution for this category: Continue with Mark di Suvero. Read other living Queens authors extensively for a workshop I hope to hold, with grants I hope to be granted.

Fiction

Five Tuesdays in Winter – Lily King

The Last True Poets of the Sea – Julia Drake

The Latecomer – Jean Hanff Korelitz

An Honest Living – Dwyer Murphy

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy – John Le Carre

Mercury Pictures Presents – Anthony Marra

Fellowship Point – Alice Elliott Dark

Natural History – Andrea Barrett

Shrines of Gaiety – Kate Atkinson

About Face – William Giraldi

Trust – Hernan Diaz

Trust Exercise – Susan Choi

I was surprised to see so few novels on my list, again, The Power Broker took up a lot of my summer. I was sad to leave the Lily King and the Kate Atkinson off my top ten list, but the memoirs below just nudged them out. The Marriage Portrait is in the queue.

Reading resolution for this category: See Queens authors, above. Otherwise, I will probably graze indiscriminately.

Memoir

Bluets – Maggie Nelson

H is for Hawk – Helen MacDonald

The Outrun – Amy Liptrot

Also a Poet – Ada Calhoun

The Lost Children of Mill Creek – Vivian Gibson

Easy Beauty – Chloe Cooper Jones

The Odd Woman and the City – Vivian Gornick

Reading resolution for this category: Don’t really have one? Crying in H Mart is waiting for me at the Astoria Library.

Essays

Animal Bodies – Suzanne Roberts

Orwell’s Roses – Rebecca Solnit

Like Love – Michele Morano

Hysterical – Elissa Bassist

Festival Days – Jo Ann Beard

All the Leavings – Laurie Easter

Bright Unbearable Reality – Anna Badkhen

Reading resolution for this category: I hope to review more in this category. I focus on collections published by indie and university presses.

Craft

Craft in the Real World – Matthew Salessas

A Swim in the Pond in the Rain – George Saunders

How to Write One Song – Jeff Tweedy

Reading resolution for this category: I am starting 2023 with a poetry workshop which has two rather daunting required texts, so, dare I say, I am good here?

Other nonfiction

Islands of Abandonment – Cal Flyn

The Strange Case of Dr. Couney – Dawn Raffel

Reading resolution for this category: I realize that this category is composed of writers with whom I took workshops in 2022, both of whom were super-kind and thoughtful.

Poetry

The Owl Was a Baker’s Daughter – Gillian Cummings

Long Rules – Nathaniel Perry

Reading resolution for this category: More, more, more.

Cozy old things and mysteries

Cheerfulness Sets In – Angela Thirlkill

The It Girl – Ruth Ware

The Madness of Crowds – Louise Penny

Dying to Tell – Robert Goddard

Reading resolution for this category: this is the “something fun to read” category. It defies resolve.

Happy reading in 2023 to all!

Petrichor!

“Let me tell you about winds,” Almasy says to Katherine Clifton as they shelter in a car from an Saharan sandstorm in The English Patient. “There is a, a whirlwind from southern Morocco, the aajej, against which the fellahin defend themselves with knives.”

I’ve been thinking about The English Patient because it’s one of my movie obsessions but also because I am in the room above the kitchen in the old house here, part of the original structure, a sheep shed, that was all that was here when the owner, Georgina Howard, bought the property. This house reminds me of the villa where Nurse Hana shelters with Almasy, now the English Patient, to allow him to die in relative peace. As the medical convoy moves on, Hana watches from a high window in the villa, chopping off her long hair into a chic bob the way women do in the movies. Disparate characters come and go, a thief called Caravaggio, a Sikh bomb defuser and his sidekick Kevin Whately (that is the actor’s name, I only ever think of him as Kevin Whately) all with their different knowledge, expertise, striving and grief. They come together for a time, and then they part ways.

Let me tell you about winds.

In my room with its view of the roof over the dining room, and then of the valley beyond, I heard the winds around dawn. The nearby wind sounded like the whoosh of the ocean. The approaching wind sounded like a rapidly-arriving locomotive. Not a whirlwind from southern Morocco – Morocco, like all the rest of the world, is far, far away – but a fierce eddy from somewhere that, when it arrived, bent the trees long ago matured into strange undulations like modern dancers.

And then it raised itself up and away.

A few days ago we had a straight, hard rain, after a thrilling prelude of thunder that purred and echoed across the valley. I grated cheese in the kitchen with a keen eye on Chef Carol, who disguises her expertise beneath a mask of amiable vagueness. What’s in the risotto? “Oh, it’s got some shallots and some . . . I chopped . . . did we say 7:15? With risotto, you have to be very precise.”

Outside, the rain stopped. Georgina thundered down the stairs and swept into the kitchen. She is not one to enter a room with hesitation but strides into the action mid-gesture with an urgency to impart, like a herald in a play. But you would not expect a docile demeanor from someone who twenty-odd years ago saw a Basque shepherd’s hut and willed into being a creative manse (or, in Basque, etxe). The central courtyard between the houses is a kind of stage, one where I would happily set a play, a romantic farce, if I wrote plays happily, which I do not.

Georgina cried, “Elizabeth! There is a word for the smell of the earth after the rain! Petrichor!” She rolled the R, so I thought the word must be Spanish or Basque. “Petrichor! From ‘petra,’ meaning earth and ‘cor,’ meaning . . . oh . . .”

From ichor, the term used to describe “the fluid that flows like blood in the veins of the gods” in Greek mythology. According to the Oxford dictionary, the word was first used in a 1964 article written by a group of scientists, which is why we have never heard of it.

“How would you use it in a sentence?” asked one of the writers when we brought petrichor along with the risotto to the dinner table.

I couldn’t think of how to use “petrichor” in a sentence that would not also include the words “smell” or “rain,” which tells me this was not a word clamoring to be coined. I also wonder how these scientists, finding the phrase “the smell of the earth after it rains,” insufficiently pithy to their needs, fell so easily onto “ichor.” Now there’s a word I’d like to use in a sentence. “How do I get this ichor stain out of my dress?”

There is a laurel tree embedded in the patio courtyard. Georgina constructed the patio around it, decided that the tree would be part of the family. In Greek mythology, Daphne, pursued by Zeus, transforms herself into a laurel tree to preserve herself from his lust and other ickiness.

The poem The Laurel Tree by Louis Simpson contains these lines:

“Is there a tree without opinions?/Come, let me clasp you!/Let me feel the idea breathing.”

And ends with these:

“The dish glowed when the angel held it./It is so that spiritual messengers/deliver their meaning.”

Xavier, my Savior

“Don’t you love her accent?” said the Irishwoman to the Brit.

She could only have been talking about me, since I was the one talking. I had been the one talking, truth be told, for quite some time, a jet-lagged dialogue fountain since the five of us had arrived at the Pyrenean Writing Retreat and been revived with a glass of wine (or several). I’d arrived in San Sebastian on Sunday, after quite a long journey that began in Astoria when I dragged my suitcase to the Q102 bus stop, took the bus to the E train, the E to the Airtrain, the Airtrain to the airport, JFK to Madrid, Madrid to Bilboa, then a bus from the Bilboa Airport to San Sebastian, where I was once again dragging my suitcase through a charming, unfamiliar town, where I was thoroughly lost.

“Is easy!” the text from the hotel read. “Cross the river to the Cathedral Buen Pastor, go straight to basilica Santa Maria and go up stairs we are in calle mari 21 very easy.”

It wasn’t easy. My phone was dying because I hadn’t had time to recharge it at the Madrid airport since I spent 90 minutes in line to get into Spain. I didn’t see any stairs and I mistook one basilica for another. Furthermore, despite several weeks of diligent study on Duolingo, my Spanish was crap. I could talk about universities and professors, drinking coffee and having a tall daughter, but I couldn’t ask for directions.

The wide avenues and plazas were full of families out to tire the kids on a Sunday afternoons and pleasantly tired, painted marathon runners. Cafes bustled.

“Perdon, hablo ingles?” I asked a passing family.

They didn’t really, but they helpfully called the hotel, and then haltingly told me that it was a 20 minute walk, which I refused to believe. (It was.) I was handed off to a man with a bicycle, and then I handed myself off to a man I stopped (“Perdon, hablo ingles?” “Yes, of course.”) who happened to be an English teacher. He delivered me to the door of the hotel, which was by then worriedly awaiting my arrival, since the call from the family. They had called me to check on my progress but of course, my phone was dead.

I was so grateful to the English teacher – Xavier, my savior – that I gave him the copy of CENSORETTES I had brought along on the trip in case any of my fellow students at the retreat wanted one. This left me with two books, THE GREAT GOOD PLACE by Ray Oldenburg, which is research for the dog café project, and THE ART OF SYNTAX, part of Greywolf Press’s THE ART OF series. And, of course, THE POWER BROKER by Robert Caro because you can’t write a history of New York City, even a tiny fragment of it, without referencing Robert Moses. One of his great works, after all, is the Triborough Bridge, which ends in Astoria. I downloaded it as an Audible book, my second-ever audiobook. It is 66 hours long and of course, it is eating up massive amounts of space on my phone. Hence, it keeps dying.

The next day, another bus brought us deeper into the heart of Basque country, and then we were collected by van and brought to the retreat, which is unspeakably lovely.

After a night of chatting, I fell into the bed of my room above the kitchen, a charming room that made me feel like some intrepid mid-century traveler, a female Patrick Leigh Fermor.

This morning we had our first workshop, with the savvy and kindly Diana Friedman. The topic was SETTING. She generously used the opening of CENSORETTES as an example of an effective setting. My fellow retreaters were very kind, but I had no copy to give them, thanks to Xavier.

But at least now I can say I have international distribution.

System of a Poet

by guest blogger Hattie Jean Hayes

Hattie Jean Hayes is writer and performer of many things, as well as a poet, but I asked her to write a guest post about her submission strategy, since she has such a successful method, far from the “dreamy, impractical” stereotype. Although I am behind on my posts for April is Poetry Month, Hattie was gracious enough to share some of her tips with my readers,

I didn’t begin submitting my work “in earnest” until February of 2021 when I set a goal of submitting a piece of writing every day. By the end of that month, I’d logged 32 submissions on the calendar. That “sprint” broke me of my anxieties or reservations around submissions, and I continued submitting through the rest of the year. My year-long goal was to see 12 pieces of writing accepted for publication; a total of 21 were accepted. I’m on track to surpass that number in 2022. If you’re trying to challenge yourself for a single month or grind on submissions all year, you can use these practices.

1. Inventory

I use two tools to inventory all my creative projects: Google Sheets and Notion. I use a spreadsheet titled Creative Project Dashboard to log my in-progress and completed projects, including short stories, novels, essays, scripts, parody songs, original musicals, and poems. Once I begin working on something, it’s allowed to be recorded here – if something is just an idea, it stays in Notion.

Every category of project gets a different sheet, and every sheet has different columns. My stories and essays, for example, get these columns: title, status (in progress, complete, awaiting feedback, editing), synopsis, length, and where I’ve submitted it. The poems get a similar treatment, with the synopsis column replaced with a “spawn point” signifier, so I can remember if something was first drafted during NaPoWriMo, a workshop, etc.

Inventorying my work allows me to track where I’ve sent things, and it means no project is forgotten. There are hundreds of items listed in my document, and when I’m putting together a submission for a journal that will review five or six pieces, it’s helpful to have a list of all my work, so I can say “Wait! I haven’t sent that one out in forever and it totally fits this theme!”

I log all my projects in Notion, a note-taking app/website similar to Evernote. Just use whichever productivity app you’re likely to actually use. I like Notion because I can easily create and move different “pages” in that dashboard. I keep a list of ideas for each category of project, and I put early drafts of the projects themselves in Notion. I really like the flexibility to use dashboards in Notion to track where I am with revisions, or record a bunch of feedback from a workshop and see it at a glance. This is not an ad for Notion, I just like it!

My Notion also has lists of all my accepted and published work, so when these pieces go live, it’s easy to copy and paste the live links onto my website. I have a page in Notion where I record third-person biographies of various lengths since this is something you need to have on hand for submissions.

2. Research

I don’t rely on Submission Grinder or Duotrope to find and record submissions, only because I find it overwhelming. Sometimes I use the aggregators on ChillSubs.com or in Submittable to look for open journals, but that’s usually when I have a specific piece that hasn’t found the right home, and I need to expand my view a little.

My primary means of finding places to submit are social media. I’m in a submission group on Facebook that introduces me to a lot of new journals, and I use Twitter’s bookmarks feature to flag journals I want to read and submit to.

I have a bookmarks folder on my browser for lit journals, and when I make a new bookmark, I name it “SUBMIT XYZ TO [JOURNAL NAME]” so I’m not confused about the bookmark later. If there’s a journal I’m eager about, and the submission window isn’t open, I set a calendar reminder – with the name of the piece I want to submit – for the day submissions open.

I don’t think you need to be a devoted fan of a literary journal to submit to it, but I do think you should get a feel of the tone and some of the published work. I think I’m most successful when I’m mindful of how my writing will fit a particular journal’s readership. My “best” writing isn’t always the best for the job.

3. Submit

This is probably the most customizable part of the process. When it comes to actually submitting, YMMV! Do you like month-long “sprints” where you send work out every day, or even shorter, day-long marathons? Do you want to fill your calendar with reminders of submission windows, and submit as they open up? Or are you going to focus on one piece of writing, and shop it around until it’s snapped up?

Whatever works for you is good! Make sure that you follow guidelines about submission formatting, and respect any rules around simultaneous submissions. Consider creating a document like mine for short bios/publishing history.

4. Index

Indexing your writing is just inventorying, again. Once you’ve submitted a piece, index the places you submitted to. There was one poem I submitted to 40 different journals in 2021. By the time it got accepted, I had 9 journals still considering it, and it was so handy to have a list of journals that needed to receive that sweet, sweet withdrawal email.

Log your kudos: were you nominated for a prize? Did your mentor say something complimentary about the piece? Put it in there! If you decide to stop submitting a piece while you revise it, make a note about your different drafts. Once you place it, you’ll want to remember the “before” and “after” so you can see what changed. And if you decide to axe any pieces, consider indexing them into a “graveyard” where they can be cannibalized into new writing later on. I began logging my projects this way in 2016, so I have six years’ worth of ideas (good and bad), drafts (good and bad), and completed pieces (mostly good! some bad) on record. That makes me a hell of a lot more confident when it comes to getting published, and when I get rejected, it’s another data point.

Hattie Jean Hayes is a writer and comedian, originally from Missouri, who now lives in New York. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Hobart, HAD, Janus Literary, Sledgehammer Literary and the Hell is Real Anthology. She is working on a novel and several much sillier projects.

Recent Comments